30% Off Annual & Gift Subscriptions, a Reader Survey + Most Popular Posts of 2024

It's a busy Cyber Monday.

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation

I don’t do New Year resolutions, vision boards, or plan much further than my next dinner, but I know for certain that I want to focus more on writing this newsletter in the upcoming year. Besides the sheer joy of writing, I love the community that has formed and the discussions we are able to have here. Thank you so much to everyone who is reading, engaging, and helping me form the virtual French salon I have always dreamed of.

For this Cyber Monday, I am continuing to offer my biggest sale of the year on Substack, with 30% off annual subscriptions + a gift option for all your friends and relatives that enjoy photography.

30% Off Annual Subscriptions + Gifts

If you have a minute, I would love to meet you and hear about your relationship with photography and about your experience with the newsletter. Please answer as many or as few questions as you’d like.

Ever year, I look back at my most popular posts to see what resonated. In 2024, it was a newsletter about work for exposure in photography, which was re-shared over a 1000x both here and on Instagram.

“We offer full credit for the publication, but we unfortunately do not have a budget for fees, as it's a journalistic piece about the history.”

Another common trope is making the project seem noble, therefore above petty mercantile concerns. This request, though, is particularly inane since neither documentary nor archival requests are ever exempt from licensing.

DON’Ts - Photos of children or the elderly in exotic locations — This is one of the most enduring visual tropes (thank you, National Geographic), beloved by (mostly male) photographers traveling to (warmer) countries armed with a camera. Photographers flock together on photo tours that descend on an unsuspecting town in a hunt for “slices of life” or “authentic culture.” In photo form, that translates to close-up portraits of older people or photos of local kids playing barefoot. The most offensive thing about such visual colonialism is that the images are excruciatingly boring.

I wish I could say there was a eureka moment that made me grasp who I am as a photographer. There wasn't. There was, however, a slow, somewhat liberating (if un-cathartic) realization that my personal style was macramé-d out of the stuff I stole from everyone and everything and that the meaning of “originality” is malleable.

Every well-meaning compliment of “painterly” to a photograph makes me recoil. By emphasizing a higher point of reference, the analogy is unintentionally patronizing to photography. But comparing a painting to a photograph carries the opposite effect: it is almost always meant as a put-down. Photorealism is often consigned to the lower tier of painting, while photographs that mimic the aesthetics of the Renaissance are elevated into the status of “art.” I, personally, never want to see another photographic tableau paying homage to the Old Masters ever again.

For some, the act of photography stops when the camera is put down after a shoot. For others, like me, it is just the beginning. Being able to sort through hundreds of photos from a shoot and pick out 10 images is a daunting task and one that takes years to hone. To take photos and to edit them requires different skills. Both rely on “seeing,” but the former is a more laissez-faire process that’s instinctive and reflex-driven, while the latter requires hyper-focus and articulated intent.

As a photographer, I am neither a social justice warrior nor the judge or the executioner. Instead, I think of myself as a witness, not interested in regurgitating moral certainties, in celebrating or condemning, but in being present. My work has always leaned towards ambivalence, diving into foibles and ethical contradictions with glee. There is no fear of “moral contagion” when tackling subjects and themes condemned by the current culture, because photography gets interesting when its message is complex and ambiguous instead of linear and self-righteous. And without an echo of empathy, no matter the subject, a photograph is inevitably reduced to a propaganda-like facsimile of an artistic statement.

I first saw Djeneba’s work pop up in The Cut, New York Magazine, and its radiant colors made me swoon. I followed her on Instagram to see what else she was up to, and when I looked closer, I still had no idea what she was photographing; was it fashion? portraiture? a conceptual project? The lack of boundaries between what are often disparate categories made me pause on each photo and weave my own stories into it.

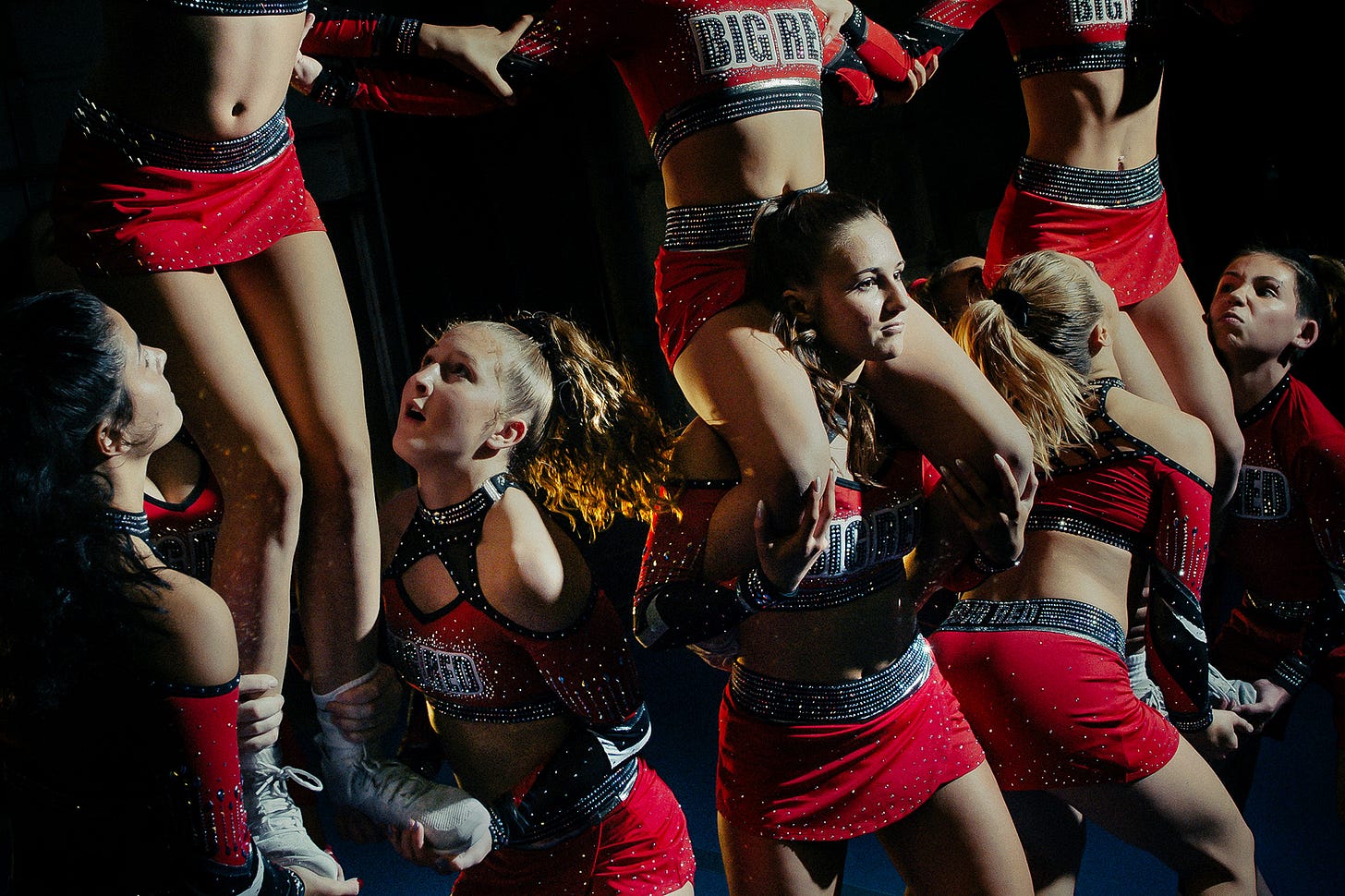

I will be sharing new work in the upcoming year, including unpublished images from a 2023 trip to Las Vegas.

Find me on Instagram @dina_litovsky.

I would love for more people to know about In the Flash. If you enjoyed reading this, please share!

Can I love you (your work and writing) any more than I already do? No.