Photography's Phallic Stage or Why Photographers Should Stop Calling Themselves "Artists"

Unpacking photography's biggest inferiority complex.

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation

Those who have been reading In the Flash from the beginning are most likely familiar with this post that was first published on Meta’s Bulletin. I am still in the process of slowly transferring those earlier posts to Substack. This was probably the most contentious newsletter I’ve sent out, but the discussion it provoked has been forever lost in the black hole of defunct digital platforms. Here it is on Substack, this time with a disclaimer: Anytime I use “should,” it’s only as serious as Jonathan Swift’s “Modest Proposal.”

I was scrolling through X when I came upon a question, "To all photographers out there, do you consider yourself an artist or a photographer?" This ought to be good, I thought. And, sure enough, the thread was exactly as I anticipated. Most people emphatically rejected the term "photographer" as if it were a derogatory mark of a lower caste. Some seemed insulted to even be asked, "Of course I am an artist since I don't shoot weddings!"

Ahh, weddings. The blue-collar bastard child of the photography world. There are a few worse things you can do as a professional photographer. If shooting covers for big magazines is Mount Olympus, photographing weddings is like cleaning bird droppings from the base of the mountain. Almost every other endeavor can be excused. There is dignity to be found in product photography, in boudoir (provoking a delicate mix of disdain and envy), in headshots, and in commercial work. In weddings, however, there is only derision. I've heard student photographers proudly announce that they will put themselves through school by waitressing but would never stoop to shooting weddings.

Growing up, I wanted to be a painter. A decent amount of drawing skills and the customary overestimation of such talents by my parents led me to believe that this was my destiny. But that wasn't an option in a Soviet immigrant family where, from infancy, I was designated either to become a doctor or to marry one. Yet my parents made one vital mistake. As I was about to head to medical school, my mom gave me a digital Nikon for my birthday. It was my first camera. For a very long time, my parents wished they had given me something, anything else, as I quickly abandoned their dreams of an illustrious medical career. Instead, I started shooting weddings.

At the time, no one told me about the stigma of wedding photography. The job paid well; I got to travel to destinations from Greece to Mexico, and there was a lot of free food and champagne. I thought it was glorious. Then I went to art school to get my MFA in photography and learned that I was doing my career wrong. I also learned that the proper way to call myself wasn't a photographer; it was an artist. That's when I rebelled.

In Russian, my first language, the word "artist" is used quite differently. Unless someone is working in more than one discipline, people describe themselves solely as a photographer, painter, actor, or musician. Those labels carry pride, while "artist" on its own can sound vague and pompous. It's less a way of describing what you do than giving your work value. In short, it's self-congratulatory. Even though I've been here most of my life and English is now my main language, I have never gotten over this subtle distinction. Calling myself an artist still makes me feel a bit cringey.

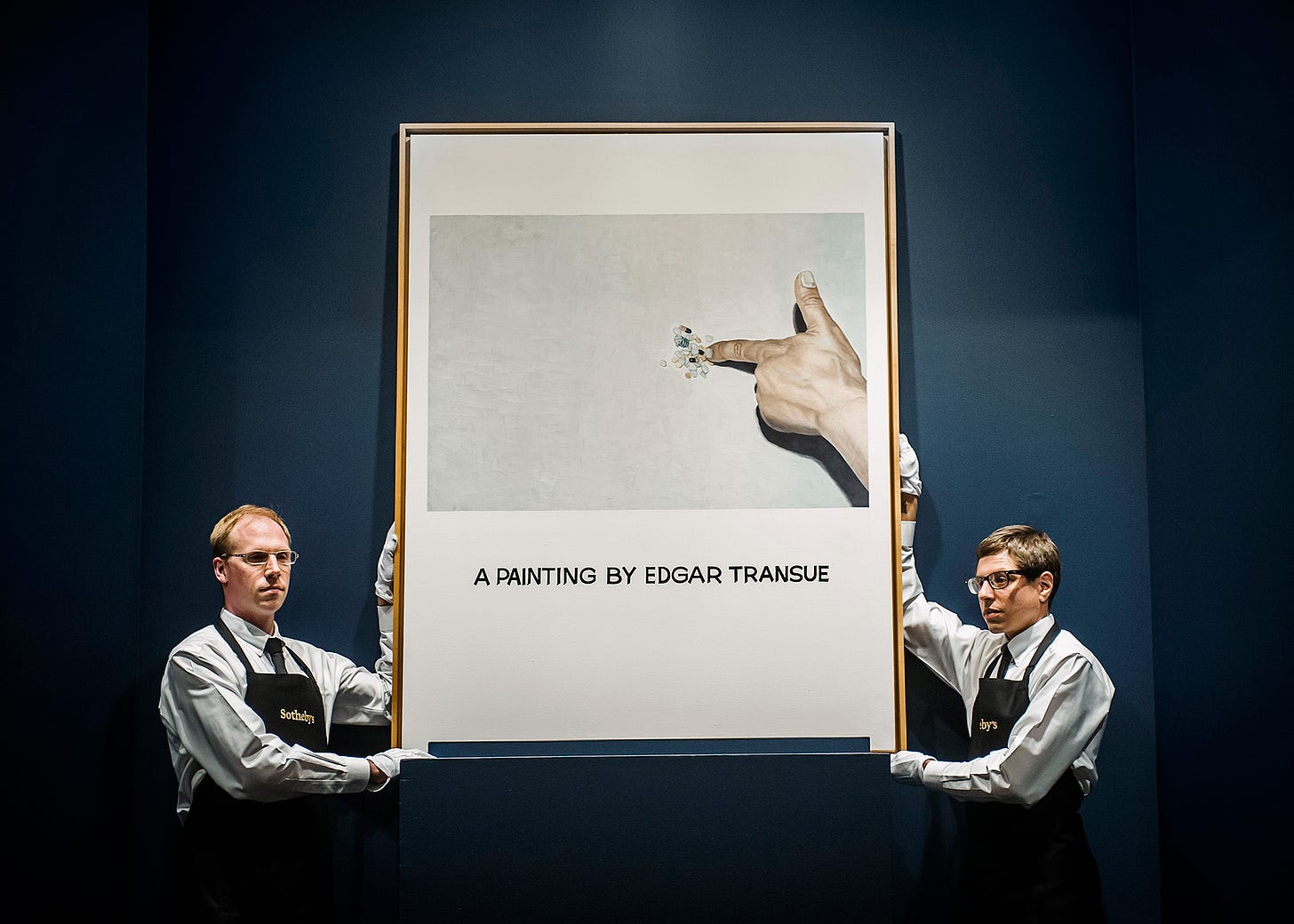

Since the invention of the first camera in the 1820s, photography has been marred by a trope that photographers are unsuccessful painters (true in my case). While that's been slowly fading, photography is just past the age of a toddler when compared to other art forms. In Freud's world, it has successfully entered the Phallic stage. Still resolving its attachment to the parent, Painting, the medium is going full-throttle through complex phases of rivalry, jealousy and identification.

There is no greater praise a viewer can pay a photograph than to compare it to a painting. The Old Masters still reign supreme in dictating aesthetic taste. Caravaggio's chiaroscuro, Rembrandt’s lighting, and Vermeer's mood remain the Platonic ideals of artistic aspirations. Painting is so well established as an art form that the standards of what is 'good' are burned in our psyche. It's Pop Culture in High Culture's clothing. People would consider you a barbarian if you weren't familiar with Picasso, Da Vinci, or Van Gogh. But I know Ivy League graduates who can't name a single living or dead photographer. And it's no wonder. Photography is not yet part of the cultural curriculum. The Met Museum boasts a small photography room that's more of a transit point by a gift shop than a stand-alone gallery. Out of hundreds of art galleries in NYC, only a handful specialize in photography, and when they do, it most often looks like painting.

Every well-meaning compliment of “painterly” to a photograph makes me recoil. By emphasizing a higher point of reference, the analogy is unintentionally patronizing to photography. But comparing a painting to a photograph carries the opposite effect: it is almost always meant as a put-down. Photorealism is often consigned to the lower tier of painting, while photographs that mimic the aesthetics of the Renaissance are elevated into the status of “art.” I, personally, never want to see another photographic tableau paying homage to the Old Masters ever again. But it's not surprising that photographers gravitate towards imitating Painting while trying to compete with it for fame and glory. We are still clinging to the mother skirt of the Old Masters, terrified to let go, uncomfortable to call ourselves merely photographers and not "artists."

Photography exists in a strange space, torn between its allegiance to the past and the possibilities of the future. To let go of the tyranny of Painting we need to get through this damn Phallic stage first. Photography is kicking and screaming and throwing hissy fits as it makes its way through Instagram to imminent dominance as an art form.

And weddings? Their bad reputation reflects photography's insecurity with itself. Shooting weddings is work for hire, but the client is the hoi polloi and subject is a manufactured, bourgeois celebration of consumerism. The worst part is that it pays too well to be considered a proper vocation for a "starving artist," a romantic ideal passed down to us from painting. As a novice photographer, I learned a whole lot from my wedding bootcamp: how to compose, how to experiment, how to direct a group of people and how to stay creative under pressure. Weddings were an invaluable part of my education as an artist.

Just joking.

I am, quite proudly, a photographer.

Find me on Instagram, @dina_litovsky

Same for me, photographer is just fine, just like "photo" or "video" is better than "content". Let's be precise!

Good essay, highlighting the cultural influences in the meaning of words!

Some well-known photographers who considered themselves more like photographers than artists:

Walker Evans: "Good photography is unpretentious."

HC-B: For me, the camera is a sketchbook, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity."

Stephen Shore: "I wanted to make pictures that felt natural, that felt like seeing, that did not feel like taking something in the world and making a piece of art out of it."

André Kertész: "I am an ordinary photographer working for his own pleasure."

Alfred Stieglitz: "Photography is my passion, the search for truth, my obsession."

Personally, I do not pay too much attention to labels but see a spectrum that ranges from documentary photographers all the way to artists who use photography to document and share their art. 🍷