The Sticky Issue of Consent in Street Photography

How a lovely family image became an internet controversy

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation

A couple of weeks ago, a former student of mine, Paul Kessel, emailed me about a photograph he took on the subway of a young woman and her two children. The image has become the subject of fierce condemnation, unsurprisingly, on Twitter. Of all the thousands of street photographs taken in New York City, this one got singled out (after winning an award) for being utterly unethical and just all kinds of wrong. Creepy, disturbing, violent, gross – were some of the epithets thrown around. A photography podcast labeled him “a snake.” Incredulous, I kept on reading about all the possible ways people found to be offended by this photo. Besides accusing Paul of showing the children's faces and the woman's short dress, the ire largely concentrated on the fact that the picture was taken without the subject’s knowledge or consent.

Here is the photo (with permission)

Before I go any further — I like this image. It's a quiet, candid moment that doesn't feel remotely disrespectful, gratuitous or sexual.

What am I missing? I thought.

I continued googling and reading. One thing stood out to me: every critical comment and article focused on the woman's “short dress.” I thought that rather strange because I have worn much skimpier outfits to family dinners. Nothing about the dress seemed too revealing. The narrative of the dress started to look some kind of inverted blaming of the woman for her wardrobe choice. I found that increasingly bizarre. Who is to judge if the dress is of an inappropriate length to be photographed? The notion that a photographer should decide if what I wear is too short sounds oddly paternalistic. We are not talking about upskirt photography, that's a different and valid issue that doesn't apply here. The photo is taken straight on and nothing is revealed by a trick angle. And unless the photographer finds a way to expose someone through such deceitful methods, the discussion of the “short dress” eventually lands at the woman's doorstep, in effect, shaming her for wearing it.

That debate aside, I want to go deeper into the question of consent and the ethics of taking someone's image without their knowledge. Somewhat ironically, Paul was my student in a class that I designed and taught at the ICP called Voyeurism and Surveillance. And no, I wasn't teaching the students upskirt photography. The curriculum centered around the moral and legal nuances, questions of consent, power and ethics in art and documentary photography. I have discussed some of these issues in a previous post: Photographing Strangers, Part 2

To review, in the US, it is completely legal to photograph anyone — regardless of the subject’s age, sex or their political affiliation — if they are visible from a public space. Our legal system has established that through several court cases. Anyone who thought that Paul's image on the subway was “creepy” might be disturbed to learn of a case where the judge sided with a photographer who spent a year secretly photographing his neighbors and their two young children who were visible from a public street through their large glass windows. Here I don't really blame the critics. While the photographer is not breaking the law— clearly visible from a public space is clearly legal — the ethics of what he was doing are certainly up for debate.

I don't want to just stand behind the law and avoid thinking through the thorny ethical issue of consent. Laws are subject to continuous change and questioning. Already, in several countries, the law is on the side of the subject, limiting the photographer in terms of being able to show faces without permission. Citing the First Amendment or freedom of speech as the last word in such a debate feels like a bit of a dead-end. And that doesn't answer the burning questions — is it actually unethical to make such images, and is street photography an exploitative practice that needs to be reexamined?

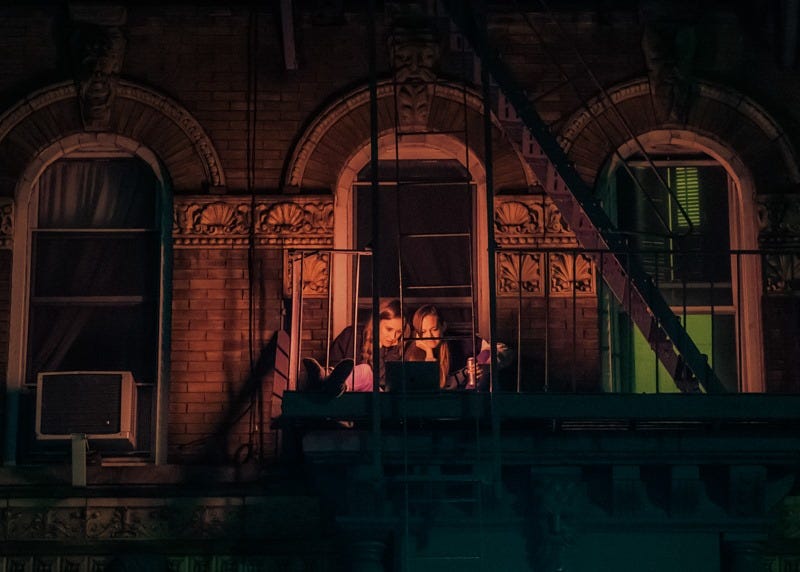

Here is an interesting conundrum I noticed with my own work. The people who get the most worked up over the ethics of certain images are NOT themselves the subjects of the photo. Over the years, many people I’ve photographed have found themselves either in publications or on Instagram. Almost everyone asked me to send them a copy, thanking me for the captured moment. Marinating on this issue, I decided to reach out to the subjects of my recent, most hotly debated photos — taken through the windows at night. Such images tend to provoke the most anger from a few Instagram critics outraged that these people are caught unaware in the privacy of their homes. I was able to get in touch with three of the subjects, two of whom are young women. I asked if any of them felt, even slightly, uncomfortable that I took those images. None had any issues with the images being taken. One told me, “We were on a fire escape lit up on St Marks Place, so not really a place to expect privacy.”

I welcome a conversation about consent in photography. This is a topic that is vital to keep in mind. Having a camera doesn't give the photographer carte blanche to ignore the question of who is being photographed, where and why. Every image should be a choice, made over and over again, by an individual acutely aware of their purpose and intentions. But I find two major issues with the way the most clamorous voices frame this debate.

One. "Consent" seems like an easy concept, but it's really not, at least not on the street. It's a bit of a Catch-22. Asking for permission before a photo is taken immediately nullifies any possibility of a candid moment. And asking for it afterwards almost guarantees you will be turned down. Even I, as a photographer, would feel suspicious if a stranger came up to me saying they just took my photo and would like some kind of retroactive permission. This raises so many questions that almost any person, probably in a rush on their commute, would inevitably just say "No." Who are you? Where is the photo going? Can I see it? As for having them look through the images, that’s a very bad idea. There are always a few outtakes, and I wouldn't know which image, if any, will reveal itself as "the one" until I sit down with the photos later. Giving the subject a power to decide what gets deleted in camera eliminates any such possibility.

Two. People who don't want their image taken by a stranger often confuse strong personal preferences with ethics. But for an action to transcend individual discomfort and enter the netherworld of immorality there has to be both a strong societal consensus as well as palpable, real-world harm resulting from it. There are many behaviors, like inappropriate touching, which our society has unanimously determined to be flat-out wrong. Being photographed, irrelevant of consent, is, as of now, not one of them. While it may seem intrusive to some, there is nothing inherently dangerous in the mere act of photographing people, children included, in the anonymity of a public space.

We live in an era where hundreds of surveillance cameras are recording our every step – on the sidewalk, in the subway, inside stores, hotels, elevators, restaurants — literally everywhere. There are drones overhead, cameras in everyone's phones and 'smart' sunglasses that can take pictures. When I go out, I assume that I not only could but will be photographed or videotaped by someone, or something. Being in public automatically comes with an unavoidable degree of clashing of my individual desires with the rest of the world. No matter how I feel about it, public space demands a certain contract where we allow some of our preferences for privacy to be overridden.

There is one vital difference between an impartial surveillance camera and a deliberate image taken by a photographer: intention. If a photo is meant to ridicule or expose a specific individual, that could veer dangerously close to the unethical territory. Or it could be just bad art. There are a couple of calculated, nefarious forms photography can take such as secret cameras in bathrooms or upskirt shooting, both of which are gross, obvious violations. Conflating those (thankfully) rare instances with the general practice of street photography feels reckless. It creates fear, conditioning people to consider any person with a camera a creepy predator. It also serves to disguise an individual preference of not wanting to be photographed as a broader matter of morality.

There is a constant tug of war between freedom of expression and concerns for privacy. It's not a zero-sum game, where one unavoidably trumps the other. While photographing in public space is legal, no one in the US is sacrificed on the altar of art. We are, as a society, protected against a photographer doing whatever they want with the image. Spying into someone's private space with specialized equipment or a drone is illegal. A photographer can be sued for libel if they willfully misrepresent an individual. Without a specialized consent form no image can be used for commercial purposes such as advertising a product. The law does its due diligence in safeguarding the subject, singling out those bad intentions that could expose or damage the person photographed.

The issue of consent in street photography is tricky because it's a bit of a wolf in sheep's clothing – it's really not about consent at all. What it effectively comes down to is the value of art vs privacy in our society.

Requiring consent pretty much eliminates street and most documentary photography as a genre. For some people that would be an absolutely fair price to pay. For many others, myself included, that would be a very unfortunate world to live in. I fell in love with street photography because of its vital place in our culture, reflecting our fragile reality back to ourselves. For that purpose, I allow photography the possibility of sometimes making someone slightly uncomfortable.

I will write more about the function of street photography as an art form in a future post, making room for both its deficiencies and its importance. For the time being, I will continue photographing strangers, respectfully and mindfully, without asking anyone for their consent and hoping that one day, they will find themselves in my images and ask me for a copy.

Photographing Strangers, part 1 - Introvert's guide to street photography.

Photographing Strangers, part 2 - The legal and the ethical guide.

Find me on Instagram @dina_litovsky