The "Sepia Bride" Drama and Reflections on My Sordid Wedding Photography Past

When clients and photographers clash.

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation

This week, I got sucked into a TikTok/Reddit wedding photography drama that overflowed social media to make the news, from PetaPixel and USA Today to the New York Times. The press reported on “Sepia Bride," a young woman so dissatisfied with her wedding photos that she took the issue to the people’s court of TikTok and went viral in an event christened “Sepia Gate." From the New York Times article, titled Here’s How to Avoid Hating Your Wedding Photos, I followed the rabbit hole to Alexandra Jaye Conder’s (Sepia Bride) original TikTok videos, the comment section, and YouTube videos of people reacting to the drama and didn’t stop until I finally found the wedding photographer in question and watched her rebuttal on a video podcast.

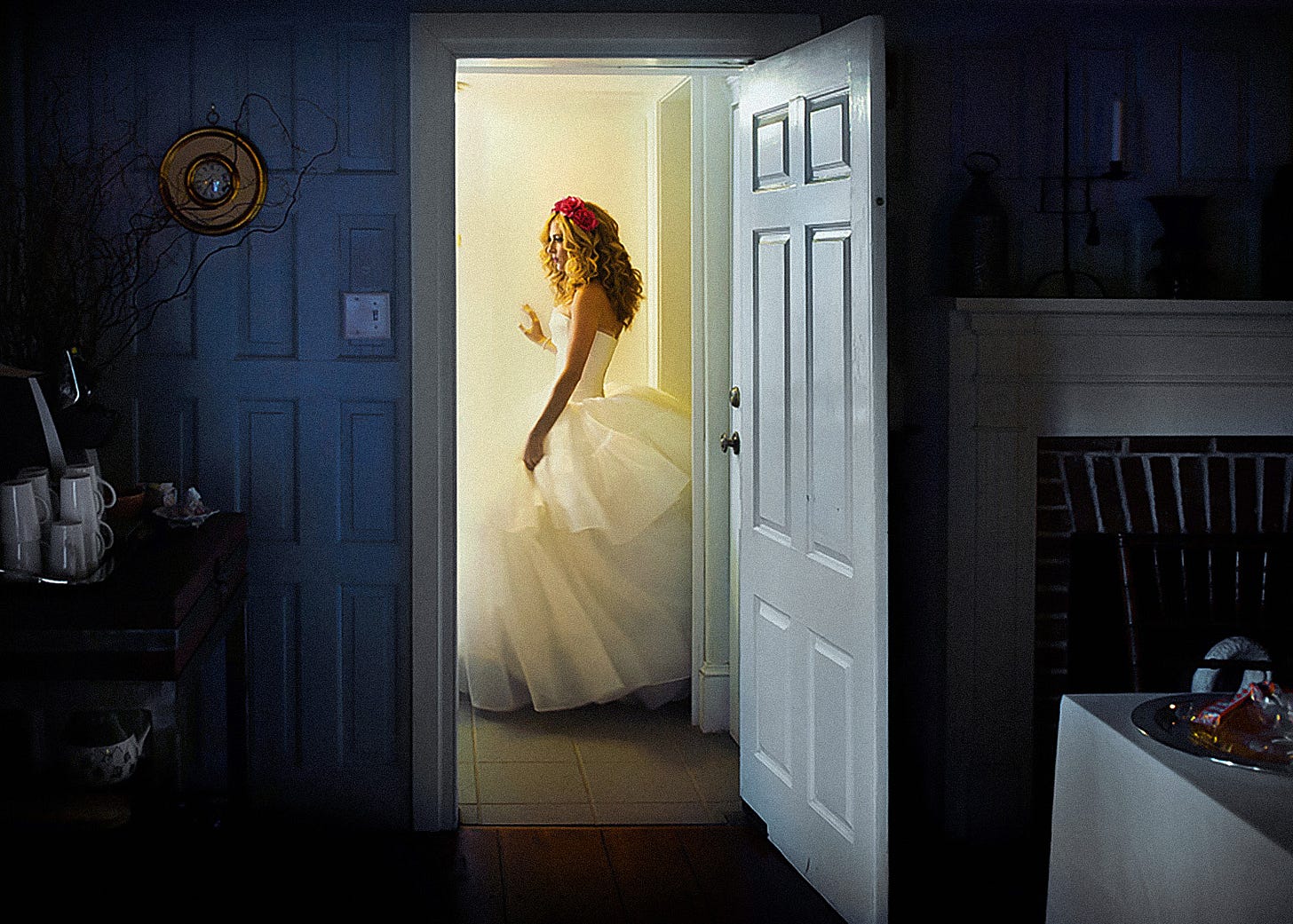

Besides the entertainment value, I was fascinated by the client vs. wedding photographer showdown because I spent the first years of my career shooting over 200 weddings. A lot of my photography practice is rooted directly in those formative years. In just a few months, I went from holding a camera for the first time to being hired as a second photographer at a wedding, for which I was paid $300 — the most money I ever made in photography up to that point. I was 23, living with my parents, in debt, and broke. Weddings gave me a way out. Within another year, I was booking my own clients in a wedding studio I ran out of my living room. By the time I turned 27, I had become the most sought-after wedding photographer (and the only woman) in the Soviet diaspora in South Brooklyn. Documentary wedding photography was becoming a new fad in this community accustomed to the heavily produced, posed style of Russian-speaking photo studios. If the bride and groom wanted something edgier and were willing to piss off their parents, they came to me.

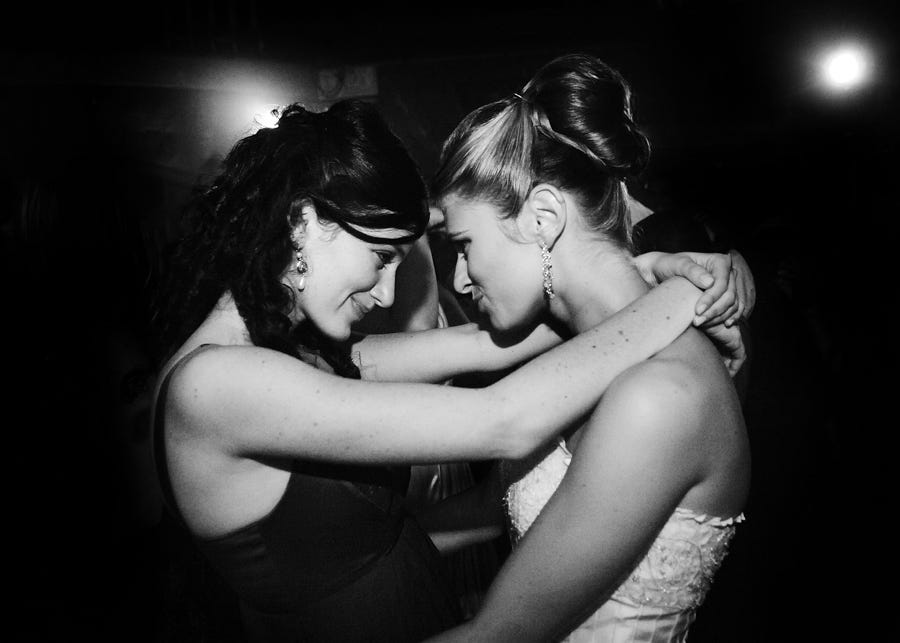

In addition to getting me out of debt, weddings were a fantastic training ground for a newbie photographer. To this day, I rely on skills acquired during my decade-long wedding bootcamp. I am often asked by magazines to work on complex shoots that involve both photojournalism and portraiture. Being fluid and able to easily morph from one style to another comes directly from my wedding days. Wedding photography is a mishmash of fashion, documentary, portrait, and still-life, blurring the lines between what are often artificial and rigid genre boundaries.

Looking through my old wedding photos, I was struck by how good a few are, but mostly by the mediocrity of the rest. At the time, I thought I was hot stuff. Now I realize I was just learning, mistake by mistake, in an environment that was much more forgiving than the editorial world. There were difficult brides, of course, but even if I screwed up one wedding, I would still book another. In the pre-TikTok universe, client drama stayed confined to wedding review sites.

Being a wedding photographer is all about appearances. The gallery on the website is the Greatest Hits album, with 2-3 photos per event in which the photographer shoots thousands. Few brides ask to see photos from one full wedding, and few photographers would oblige such a request, but it’s the best way to get a good idea about what you are getting. The most inept shooters can manage a few nice photos from an event designed to be picturesque, but it takes a professional and experienced photographer to deliver a consistent edit of 1000+ images taken in every imaginable lighting configuration. As I scrolled through my years of wedding galleries, I could see how, year by year, the number of good photos started to outnumber the bad. By the time I quit, my galleries were fire, and I wouldn’t be embarrassed to show every single photo to a prospective bride. That took me 10 years.

Which takes me back to Sepia Bride. The drama in question resulted from post-processing. Alexandra chose a photographer based on her Instagram page that had “gold-tinged” photos and was unhappy when she got her own photos cloaked in orange-sepia tones. When she asked the photographer to reprocess them for a fee, she got back photos that looked even worse and requested RAW files so she could white balance them on her own. The wedding photographer gave her a $4,000 price tag for such a privilege. Now here is where the battleground split. While some people sided with Alexandra, many photographers came to the defense of their own, claiming the bride knew the sepia style before hiring and that the photographer has creative artistic autonomy over the resulting photos. The bride was labeled a difficult Karen (a tag I hate, which the Atlantic writer Helen Lewis places in the misogynist basket).

In most cases, I would also side with the photographer. I have been on the receiving end of impossible demands in which brides forget the circumstances of the day and blame the photographer for situations out of their control. A bride once asked me for her money back because there were no posed family photos. I had to jog her memory that she refused to take any, asking me to only focus on the documentary moments and not waste any time doing formals. Another bride was unhappy because she couldn’t find a photo of herself smiling during the ceremony or party (the couple split up within a year). Having such issues is every wedding photographer’s nightmare, and even though most are resolved, it’s a stressful experience.

Looking through Alexandra’s photos, my empathy for the photographer was replaced with sympathy for the bride. The post-processing filter sucked the life out of the photos, turning green grass into mucky brown and skin into an orange peel. It seemed to be applied as a pre-set to all photos indiscriminately, discounting the differences in lighting and situations. Processing 1000+ images individually is a long and tedious process, but it is necessary to avoid a fiasco like the Sepia Bride’s" photos.

An American satirist, Jules Ralph Feiffer, famously said, “Artists can color the sky red because they know it’s blue. Those of us who aren't artists must color things the way they really are, or people might think we're stupid.” Photographers defended the sepia toning as an artistic choice and style of the photographer. Had she turned the sky red, I would have agreed. But the filter was used as a shortcut to make the photos consistent, not as an artistic device intended to transform reality. Consistency is the hardest task for any photographer shooting in bulk, especially a wedding one. The event starts in the soft window light of the morning, continues into either direct sunlight or an overcast during the bride and groom photoshoot, then into the sunset of the ceremony and the always-too-dark space of the reception. White balancing everything in post is always a nightmare, which is one reason many choose to turn their images black and white. Or sepia.

Many of my early photos relied on a similar sepia crutch to transform a boring photo into a slightly more exciting one. I thought that everything looks better when cloaked in nostalgia. This is not to dispute that there is fantastic, graphic, and emotional black and white wedding photography, just that it’s easier to appeal to an untrained eye by slathering lackluster photos in sepia-tinged art sauce. That first impression is often illusionary. Brides tend to like portfolios with a vintage treatment because there is no emotional connection to the people in the photos and the effect seems “artistic.” For all you know, that stranger’s wedding might as well have been celebrated in Pleasantville, with all colors already drained. But looking back at your own event, brides with an all-monochrome portfolio will miss the immediacy of the moment — the colors of the dresses, the makeup, the flowers, and the sky — and will earn to remember all the colors lost to post-processing.

The wedding industry has experienced a photography boom since 2004, when I shot my first wedding. At the time, working private events was embarrassing for anyone who wanted to be “an artist.” An ex-boyfriend who was a seasoned wedding pro gave me a stern warning when I entered industry: “No one goes on to have an art career after shooting weddings. It’s a trap.” When I did get into my MFA, I deleted my wedding page, changed my email, and created a new website. My identity as a wedding photographer was erased.

But photographers’ contempt for weddings has been changing. Snubbing work that pays so well is a dangerous move in an industry where “work for exposure” is an accepted concept. When I transferred from weddings to editorial, I was shocked to discover that one wedding paid as much as a seven-day assignment for most established magazines. Being a wedding photographer may not sound as glamorous as shooting for publications, but one type of work will pay your rent, while the other will pay for your lunch. As a result, many young photographers happily enter the wedding arena after graduating from art school. The industry that was once considered a client-oriented service transformed into an artistic arena.

Whenever the label of art is slapped onto something, photographers’ egos start to clash with the desires of the client. That’s what struck me the most about the Sepia bride story. The wedding industry is a Wild West of photographers who can get away with dubious practices because they are not working with seasoned editors but with regular people who rarely know what a white balance is. Ironically, these clients shell out more money for a photographer than most high-brow publications. The Sepia Bride photographer charged her client $8,000 for the wedding, a high rate by most standards. For that much money, it should be expected that the photographer is a top-of-the-line professional and wouldn't make a mistake of messing up the white balance to make the photos look both orange and underexposed, all while defending it as a stylistic choice.

Reading all the brouhaha took me back to the time that a groom noticed that the toning of my photos gave a blue tint to his black suit and asked me to correct everything. Color grading was my standard practice, but this was the first time that someone raised an issue with it. The groom was unhappy, and I agreed to go through 500 photos manually to remove the blue tint from the suit while being careful not to touch the sky or other objects around him. This took me days, and I hated every minute of it. But I knew that in the end, a wedding photographer, no matter how creative and autonomous, is shooting for the client in the same way that a magazine photographer is working with editors who have the final say over the photos. If the publication is unhappy with the edit or post-processing, they will ask you to redo it. Some, like National Geographic, require all your RAW files. If the photographer refuses, the editor will never work with them again.

That incident was about the time that I realized that I was mentally and emotionally done with weddings. Soon after, I closed the shop. Going down the Sepia Bride rabbit hole brought up many memories about my long and conflicted adventure with wedding photography. It also brought up questions about the client/photographer relationship, whether private events or editorial, and the distinction that some people place between being an artist vs a photographer.

More on that in the next newsletter.

Find me on Instagram @dina_litovsky

Thank you for sharing your experiences as a wedding photographer. I appreciate how you compared and contrasted the wants of customers and editors.

This was my favorite line, “slathering lackluster photos in sepia-tinged art sauce.”

Great post. I appreciate your candor. I've been asked to do 3 weddings. I turned each down. Despite the pay, i could not put myself through the stress of getting someone's most important day of their life perfect. I'm satisfied with the stress-free lunches I earn.