The Loaded Sensationalism of The Stringer, a Documentary That Split the Photography World

Plus 30% Off Annual Subscriptions for the Holidays

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation

I don’t do yearly resolutions, vision boards, or plan further than my next dinner, but I know for certain that I want to focus more on writing this newsletter in the upcoming year. Besides the sheer joy of writing, I love the community that has formed here and the conversations we’re able to have. Thank you to everyone who is reading, engaging, and helping me form the virtual French salon I’ve always wanted.

For this Holiday Season, I’m offering my biggest sale of the year: 30% off annual and gift subscriptions for any friends or relatives who love photography.

30% Off Annual and Gift Subscriptions

Thank you for your support and for enabling me to write pieces like the one below.

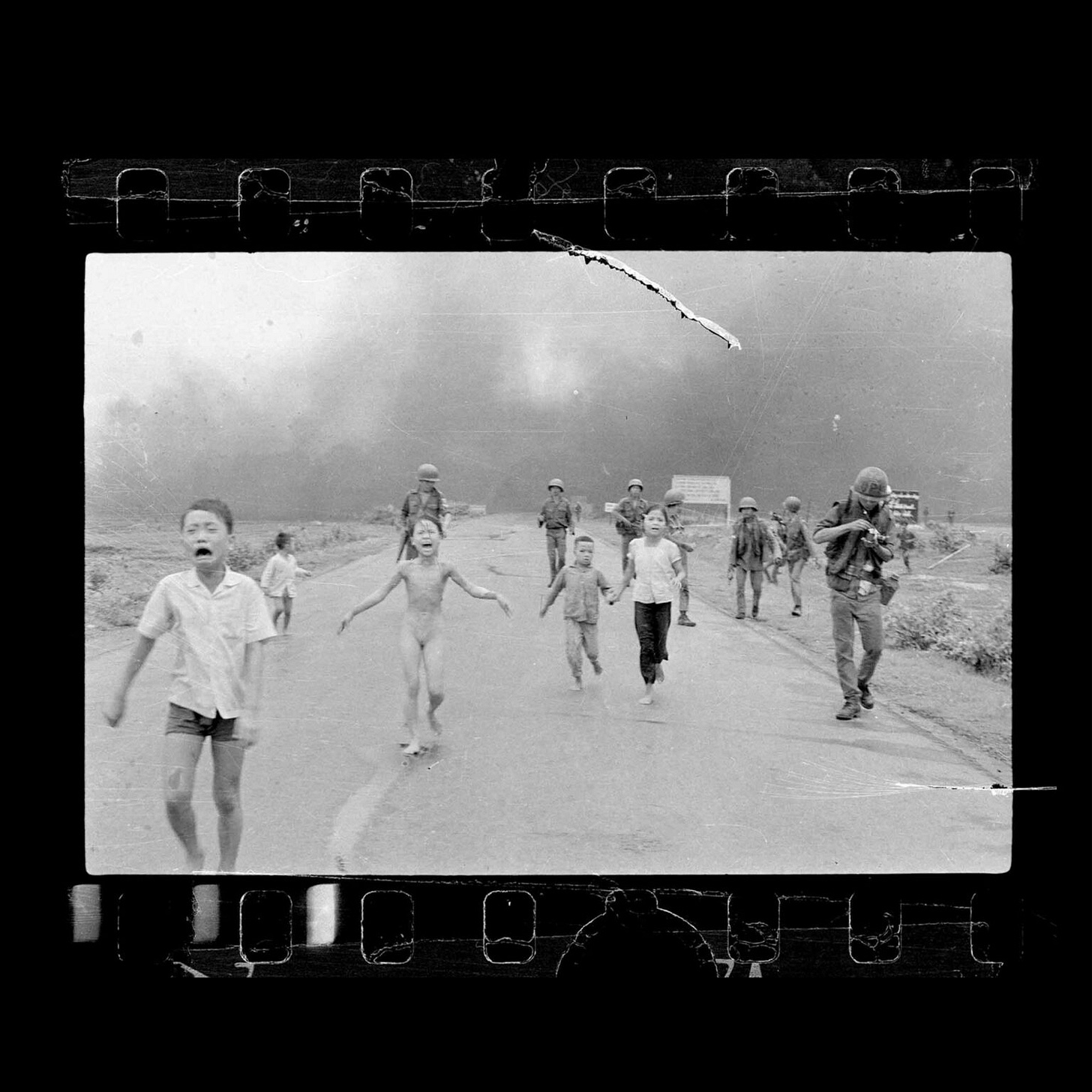

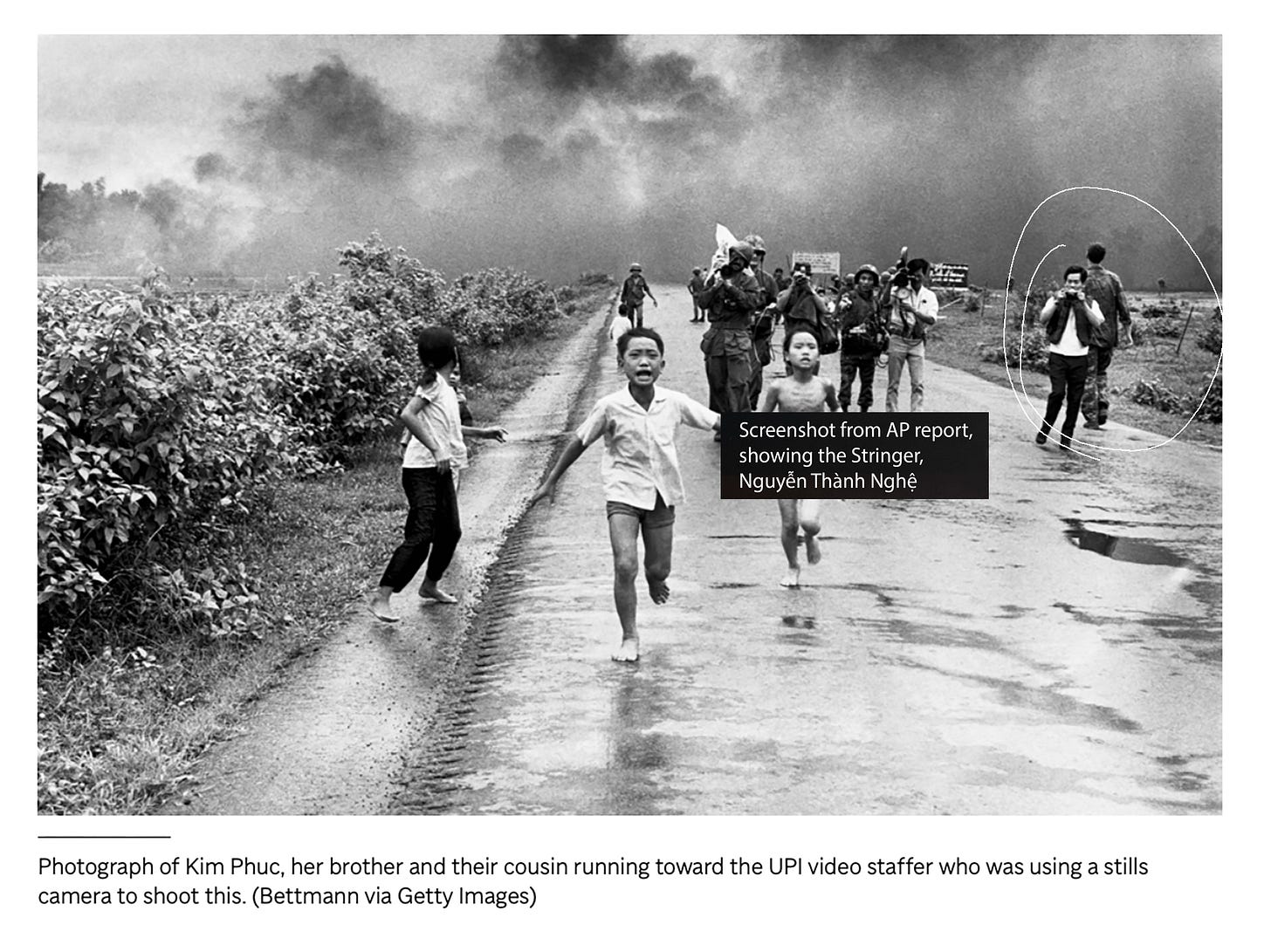

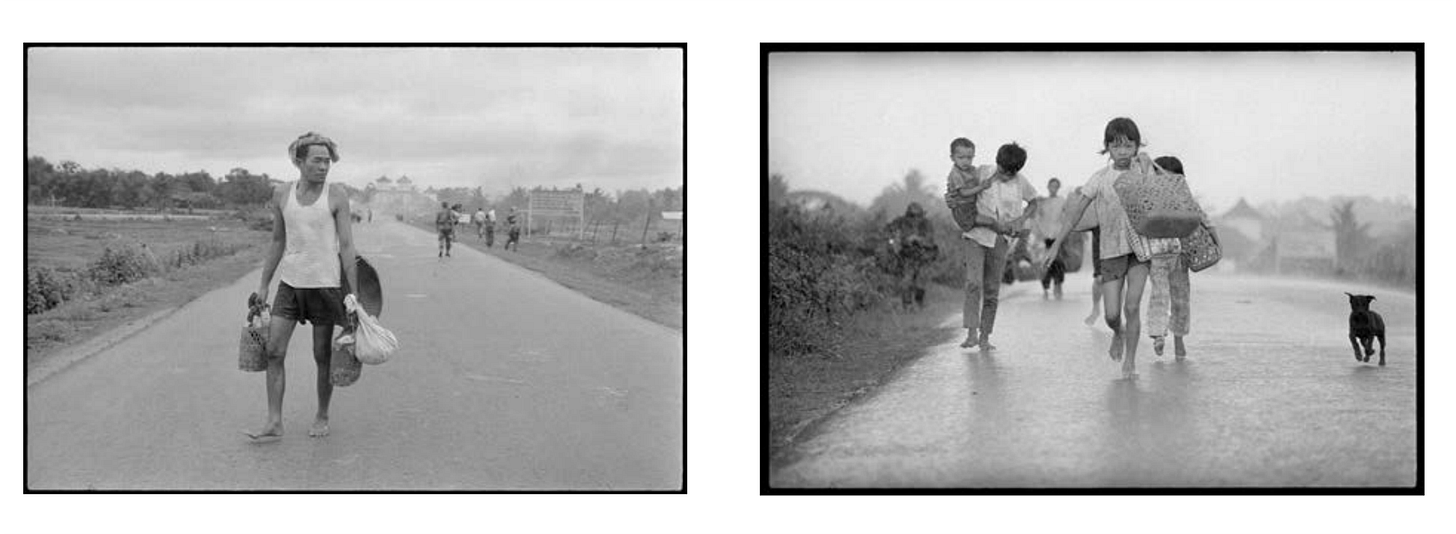

For the last year, the photography industry has been rocked by a scandal that the Terror of War, colloquially known as Napalm Girl, a famous Pulitzer-winning Vietnam War photograph taken by Nick Ut, was not taken by him after all. A documentary directed by Bao Nguyen and produced by Gary Knight, the executive director of the VII agency, claims that the photograph was willfully misattributed to Nick Ut by an AP editor and without his knowledge or consent. The agency favored the byline of an established AP photographer, Ut, over an unknown Vietnamese stringer with a foreign-sounding name, Nguyễn Thành Nghệ, who was photographing the same scene at the same time.

Such an alternative narrative of events from 1972 has been the subject of frenzied discussion on social media, with photographers tearing each other apart in their polarized support of either Nick Ut or Nguyễn Thành Nghệ. I followed those exchanges with curiosity. The film wasn’t available to the public until just a couple of weeks ago, and I wondered how people could have such strong opinions without either being at the scene or having a full grasp of the evidence. A couple of colleagues whom I respect landed on opposite sides of the divide, making the matter even more complicated. Santiago Lyon, a former Director of Photography of AP, appears in the documentary and seems persuaded by the argument, while the legendary photographer David Burnett, who worked alongside Ut that day, has been vociferous in defending him, claiming that he saw Ut take the photograph with his own eyes. In the famous words of Fiddler on the Roof,

“He’s right, and he’s right? They can’t both be right.. You know, you are also right.”

I finally watched The Stringer on Netflix this weekend. Since I have no allegiance to one side or the other, my intention was to approach it without any strong bias. For one subconscious reason or another, I was rooting for Ut when the film began, but as it went on, I was more convinced by the evidence than I expected to be.

Watching Nghệ and his daughter claim that he is the real author of the Napalm Girl is the most emotional and convincing part of the documentary. It is hard to listen to them tearfully recount their version of events without being at least somewhat persuaded. Unlike Ut’s case, where memory could falter about which specific frames could or could not come from one of several cameras he used that day, the family’s narrative is harder to reimagine. The photo was allegedly sold by the stringer to AP for twenty dollars, then a copy of it was ripped up by Nghệ’s wife to spare the children from seeing the horror, while she kept a clipping of the same image among her personal belongings. To fabricate a story like that would require an odd family conspiracy dating back to 1972.

That is where my sympathy for the film ends. Though the opening scene presents it as an investigation in search of the truth, it plays more like a prosecutor’s argument with the verdict decided from the get-go. To take away a photographer’s credit after fifty years is a really, really grave matter, yet the documentary treats it in a way that feels flippant, presenting evidence for only one side of the case.

Nick Ut himself is conspicuously absent. The filmmakers gesture toward this only once, showing a couple of text messages Gary Knight sent to Ut requesting a meeting (no response from Ut visible), then cutting to Knight waiting in a café and sighing when Ut does not appear. The moment, filmed from two angles, feels staged and a bit cringe, raising questions about what really happened. The film’s final line states that Ut has not responded to multiple requests for an interview, but for an accusation of this magnitude, it feels low-effort at best to not include anyone else who has corroborated Ut’s version of events.

A scene that unsettled me the most is the 3D recreation of the moment the Napalm Girl photo was taken, showing a nine-year-old Kim Phuc running down the road. Phuc, completely naked and screaming in pain, is flashed on the screen over and over again as the film attempts to prove that Nick Ut could not have been in the right position to take the picture. By doing so, the filmmakers exposed an astounding lack of sensitivity, with the child’s body dehumanized as potential evidence and her suffering flattened into a forensic illustration. I wonder how Kim Phuc, who is also absent from the film, would feel seeing herself used as a pawn in a testosterone-laden game of whodunit.

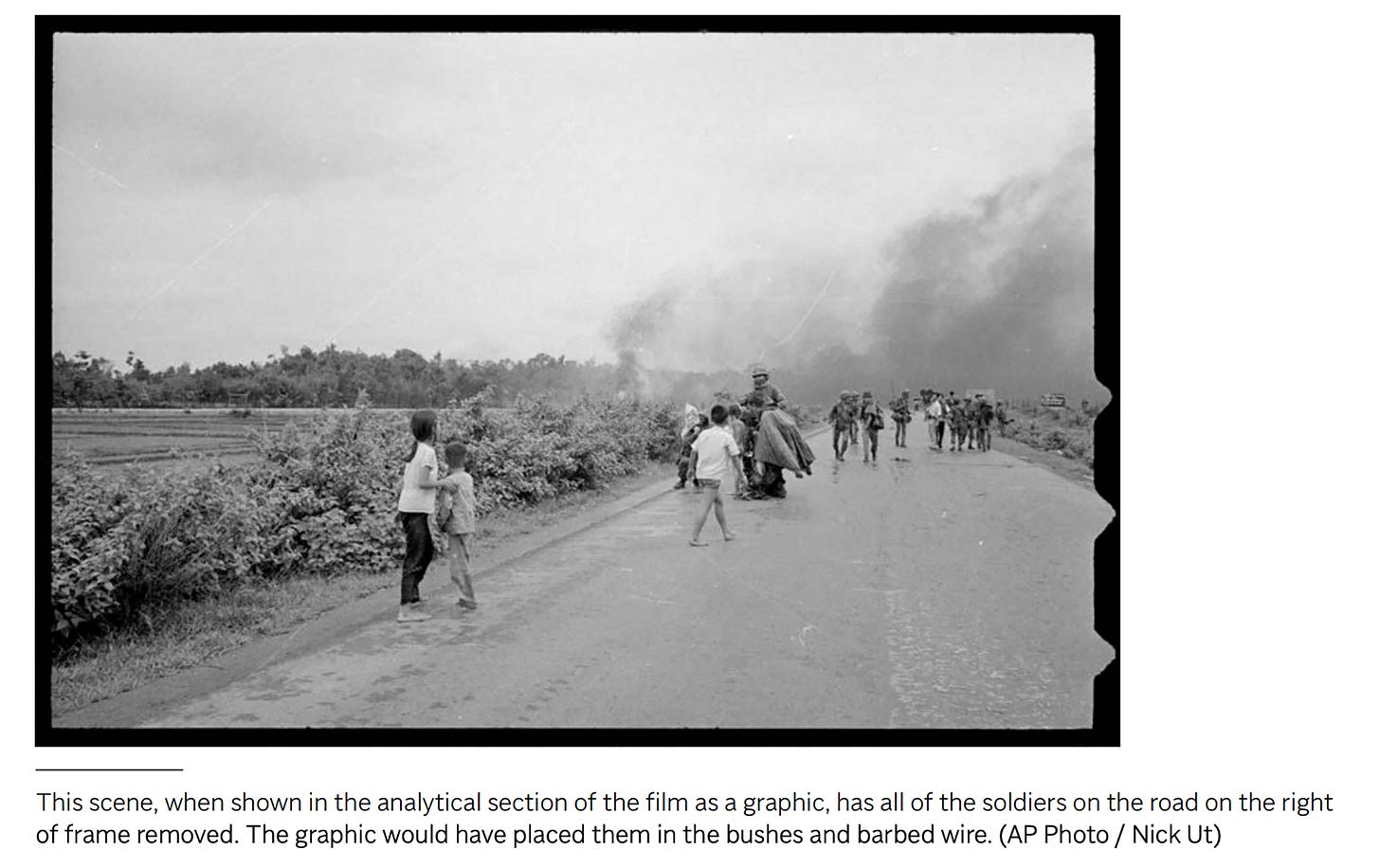

While the documentary presents this rendering as irrefutable evidence, AP has disputed the 3D model and its conclusions. After almost a year of its own investigation and a public ninety-page report, the agency argues that the render is flawed, built on selective assumptions and incorrect environmental details that make it unable to exclude Nick Ut in any definitive way. AP produced its own account of the scene through a detailed chronological sequence and photographs, which I found more coherent and easier to follow than the confusing 3D model. Although the agency’s conclusion remains unsatisfying because the physical evidence is incomplete, it does challenge the film’s smoking gun assertion that Ut could not have been close enough to make the image, stating:

“The review shows that Ut was on the road outside Trang Bang that day… carrying four cameras… that he was moving around relentlessly shooting high-quality news photos of the village … and that he was in the vicinity of where Kim Phuc and other children and adults emerged from the devastating scene… AP has concluded that it is possible Nick Ut took the photo.”

Another misleading idea in the film is its graft of the broader narrative about Western outlets favoring white photographers over local shooters in second- and third-world countries. That bias is real, but it collapses in this case because both photographers at the center of the authorship dispute are Vietnamese, and the actual power imbalance sits with Western editors and institutions rather than with Nick Ut’s ethnicity. The film doesn’t acknowledge this tension, which makes its appeal to a broader narrative of racial injustice feel like fashionable virtue signaling rather than a grounded critique of what happened in this particular case.

The lack of effort to include anyone who could speak on Nick’s behalf is glaring, and it remains the film’s weakest link. Though I was moved by the testimonies of Nghệ and his family, these are circumstantial and personal accounts. Outside of those, little verifiable evidence exists of Nghệ taking this particular image or any other photograph from the Vietnam War. The film presents no physical proof: no roll, no camera, no contact sheets, and no surviving negatives. The explanation is that Nghệ lost much of his equipment, cameras, and negatives when he emigrated to the United States with only one suitcase, which is plausible but still a tiny bit sus to any working photographer, because if our house is burning, the first thing we try to save are our negatives or hard drives. On the other side, the AP report includes two different frames of Kim Phuc running attributed to Nick Ut in their archive which visually align with his other images from the day (a subjective read, of course) — the decisive moment, the slight camera tilt, and the wide-angle composition.

So, who actually photographed Napalm Girl? After watching the documentary, reading the AP report, as well as interviews and statements from several of the key players on both sides, I can say with complete confidence that I have no idea. This strange story has too much contradictory information that is way above my pay grade. While plausible evidence exists on both sides, my biggest frustration with The Stringer is that it presents an argument against Nick Ut as unilateral and is blatant in its desire to convict rather than investigate. It leans on sentiment, with maudlin cinematic choices and leading interviews that push emotion over clarity, when I would have preferred a more objective approach and far less tugging at heartstrings.

For a photographer, losing authorship is a terrifying possibility akin to losing one’s archives. I sympathize with Nick Ut for having his authorship denied in such a public manner, and I sympathize with Nguyễn Thành Nghệ for possibly having his credit erased from the start. What makes The Stringer hard to sit with is how cruel it feels toward Nick Ut, as if the spectacle of dismantling his legacy matters more than the dignity of the photographer, who, by their own admission, was a victim of circumstance. Did the film need to exist to prove that Nick Ut did not take the photo, or could that have been handled inside the industry and with more grace? I think it could have.

30% Off Annual and Gift Subscriptions

Find me on Instagram

This is the best response to the film that I've read. I agree with everything you wrote. I've spent an embarrassing amount of time reading articles and comment threads full of dudes yelling at each other about it.

Excellent, thoughtful response. I really value your perspective and voice in this conversation. I haven't seen The Stringer, but I will watch it now with antenna up.