The Highs and Lows of Nude Photography on Album Covers

Beyoncé on a horse, Lizzo baring all, Pulp's hardcore and Azealia Bank's censorship.

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation

I taught an MFA photography class recently, where one of the students, a young woman, had a question about one of my Do’s in the Photography’s Dos and Don’ts list — “Sometimes, I miss the male gaze… I want more sexuality in photos that are messy, dirty, and dripping with desire, regardless of the photographer’s gender.”

Why would you miss the male gaze, she asked. What is even good about it? The classroom got quiet, and 15 pairs of eyes pierced me with their student gaze, expecting a thorough and revelatory explanation. But I wasn’t ready for one at the moment. Choosing my words carefully, I told the class that I don’t consider male gaze to be inherently bad, nor do I consider female gaze to be automatically good, and that it all depends on intent and execution. To show an example, I googled one of my favorite photographers, Helmut Newton, but the first image that popped up was the iconic and infamous photo of a model on all fours, on a bed, wearing a saddle. There was no way I could explain why instead of exploitative, I found the photo provocative and inspiring, so I changed the topic. But I have been thinking about the question and the possible, coherent answer ever since and have started writing a newsletter about sexuality in photography and the male gaze.

While that’s brewing, I am re-sharing an updated newsletter about sexuality on album covers, where the male gaze ranges from cringe to sublime and the female gaze rarely exists on its own terms.

One of my favorite records, Motomami by Rosalia, is also one of the most confusing album covers I've ever seen. Rosalia is fully naked, wearing a gigantic motorcycle helmet while covering herself demurely with claw-like nails like a Botticelli's Venus from hell. She seems to be toying with the many tropes of naked women selling testosterone-laden music made by male artists, but the photo itself feels like a meme created by a hungover art director after a three-day binger. As a representation of one of the most talented and unique voices in pop music, it fails.

Trying to understand why, I started thinking about the use of nudity on music albums and came up with a list of stunning successes and unfortunate mistakes by artists of all genders.

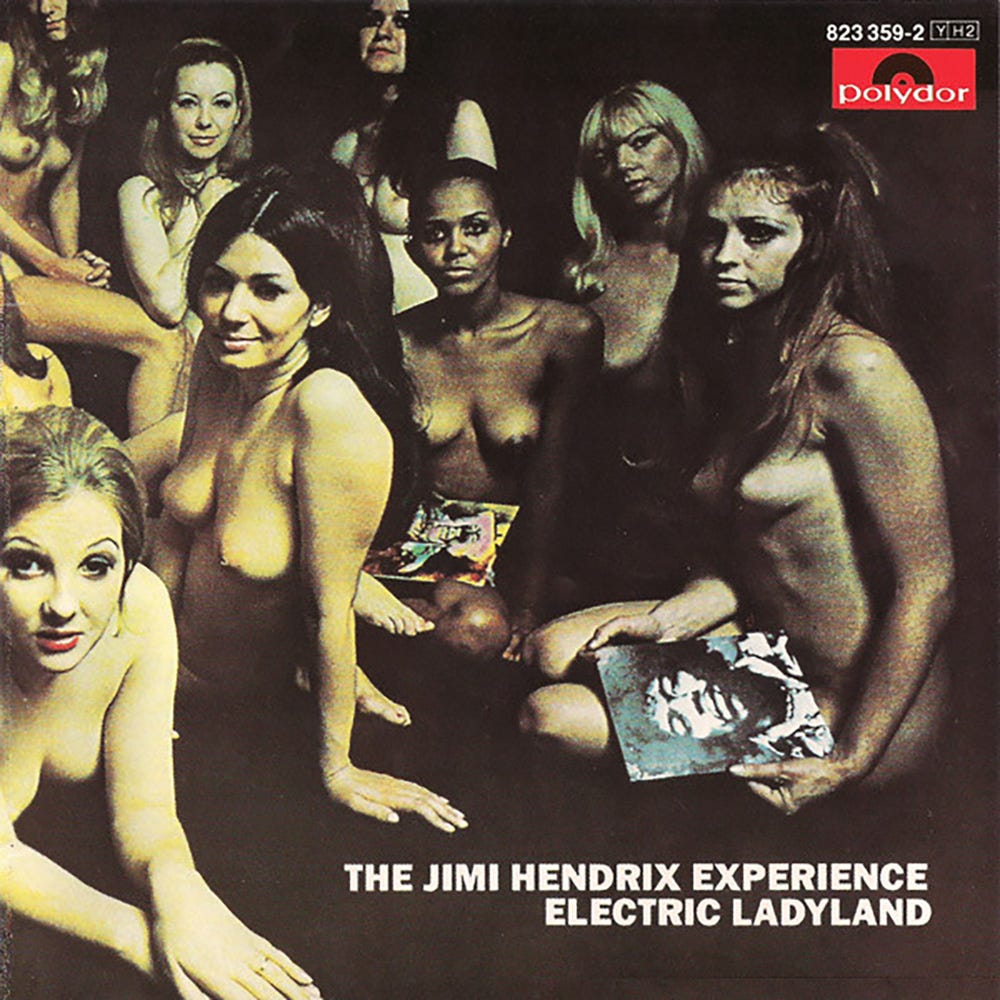

Male artists have been putting photos of naked women on album covers since the 1960s, and they range in quality and intent from provocative to irredeemably trashy. Jimi Hendrix’s 1968 Electric Ladyland is one of the most notorious early examples. The album had several covers made for different markets, with its most controversial album sleeve featuring 19 nude women destined for the UK. Both Hendrix and the critics hated the photo and doomed it to failure. They were wrong. The album went on to sell 35,000 copies in its first few days, with some people buying it just for the cover and never listening to the record.

The tackiness scale of nude covers is usually in perfect harmony with the music itself. Is it any surprise that the bloated, blatantly misogynistic 80s German band Scorpions have a whole medley of nude women selling their music that boasts lyrics like “The b-tch is hungry, she needs to tell/ So give her inches, and feed her well.” In the Soviet Union, Scorpions were elevated to god-like status because of cloying freedom anthems like "Wind of Change." Their album covers were censored so it was a shock to discover that a band that still makes many a Soviet immigrants‘ eyes tear had an album titled Virgin Killer, featuring a spread-eagled, nude 10 year old girl on the cover. It was banned everywhere except Germany (look it up at your own risk).

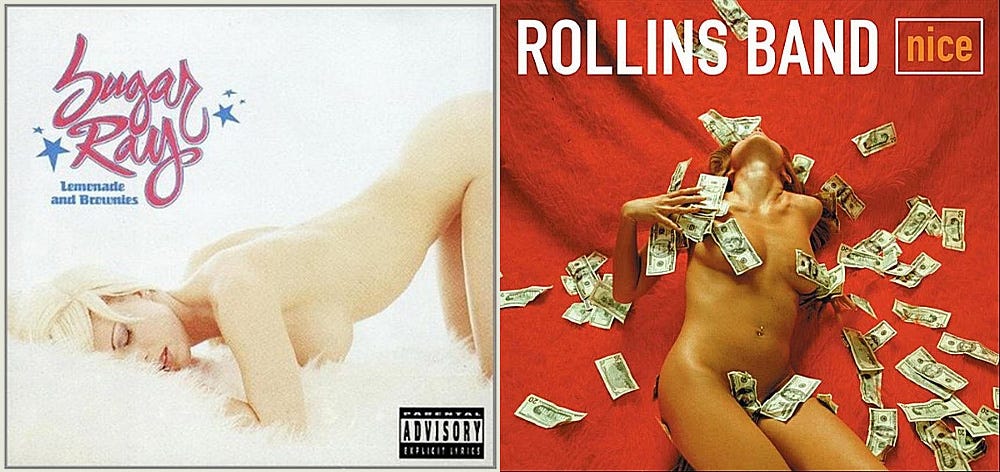

The objectification of nude women by male musicians rarely falls to the depths achieved by the Scorpions but there are a few worthy contenders, such as Sugar Ray with Lemonade and Brownies (1995) or Rollins Band with Nice (2001). Both images are crass, though the pornographic pose of Sugar Ray's image, its romantic color palette, the model's closed eyes — all make it the trashier of the two. Thankfully, it's mostly uphill from here.

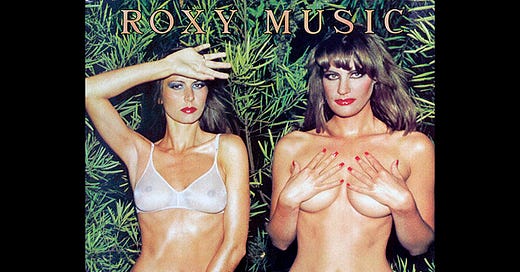

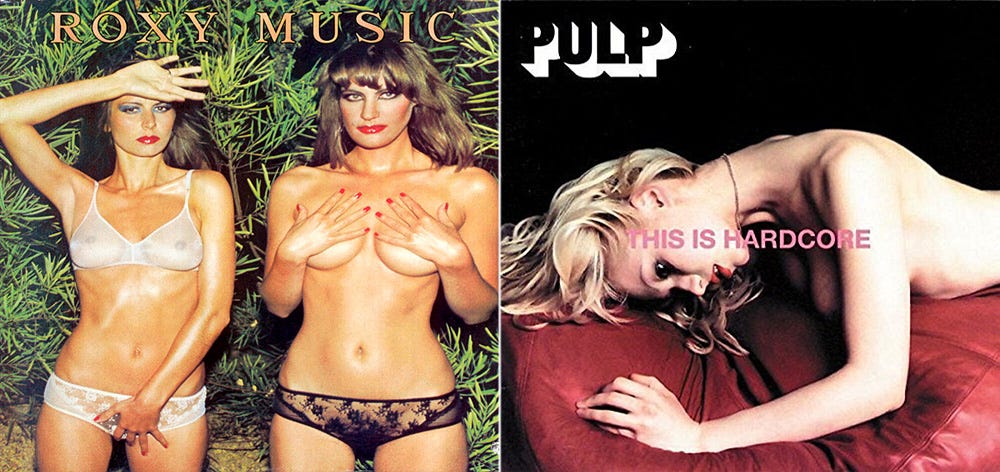

Roxy Music's Country Life (1974) teeters precariously on the edge of objectification but gets away with it because of the intense, Helmut Newton-like powerful gazes of the two women in transparent underwear. The photo is blatant in its tantalizing appeal and makes no flimsy art excuses and, I have to admit, I like this campy cover. Still, Roxy Music presents a curious dissonance. Several of the bands' albums feature scantily clad women in suggestive poses, but the music itself belies the setup of a cheap thrill — it is daring, complex and often genius.

Another one of my favorites is Pulp's This Is Hardcore (1998). Britpop's most sardonic and exuberant band didn't mince lyrics and wrote about romance and sex with unabashed detail. This Is Hardcore means exactly what it sounds like. Whatever the superficial similarities between this album cover and Sugar Ray's, the result is strikingly different. Combined with the title, the overt sexuality of the cover is intense and intentional, yet it's not the only theme depicted. The dramatic lighting and bold color, the woman's half-open eyes and the hand digging into the pillow with tension, all create an eerie effect reminiscent of David Lynch's cinematic universe. When released, advertising posters of the album were defaced on London subways with slogans such as “This Offends Women” and “This is Demeaning.” Such reactions completely missed the point. Sexuality on its own is never offensive nor demeaning. It's how the women engaged in a sexual act are depicted — presented to the viewer as passive, romanticized objects or charged with their own agency and power — that make the nuanced world of difference.

Alternative group the Pixies put a topless flamenco dancer on the cover of Surfer Rosa (1988) and obscured her with a dark vignette, sepia toning, burned out negative filter and photographic frame. Against all odds, despite the galling art gimmicks and with the help of great typography and design by the iconic 4AD label, it worked. It's a beautiful cover that holds in itself a promise of a treat that the music gleefully delivers. In contrast, the nude image by the renowned photographer Jan Saudek on the cover of For the Beauty of Wynona (1993), an album by Daniel Lanois (a singer-songwriter who sounds dangerously close to Bruce Springsteen) looks ridiculous. Why this woman is both naked and holding a small knife is a conundrum best left unpacked.

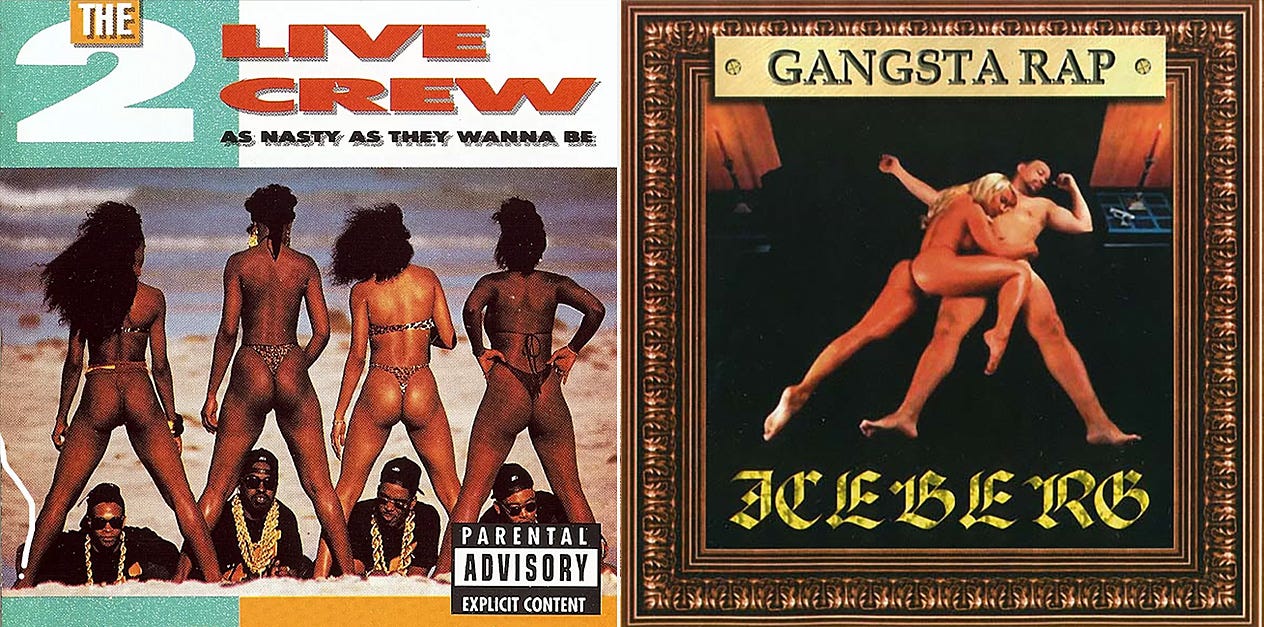

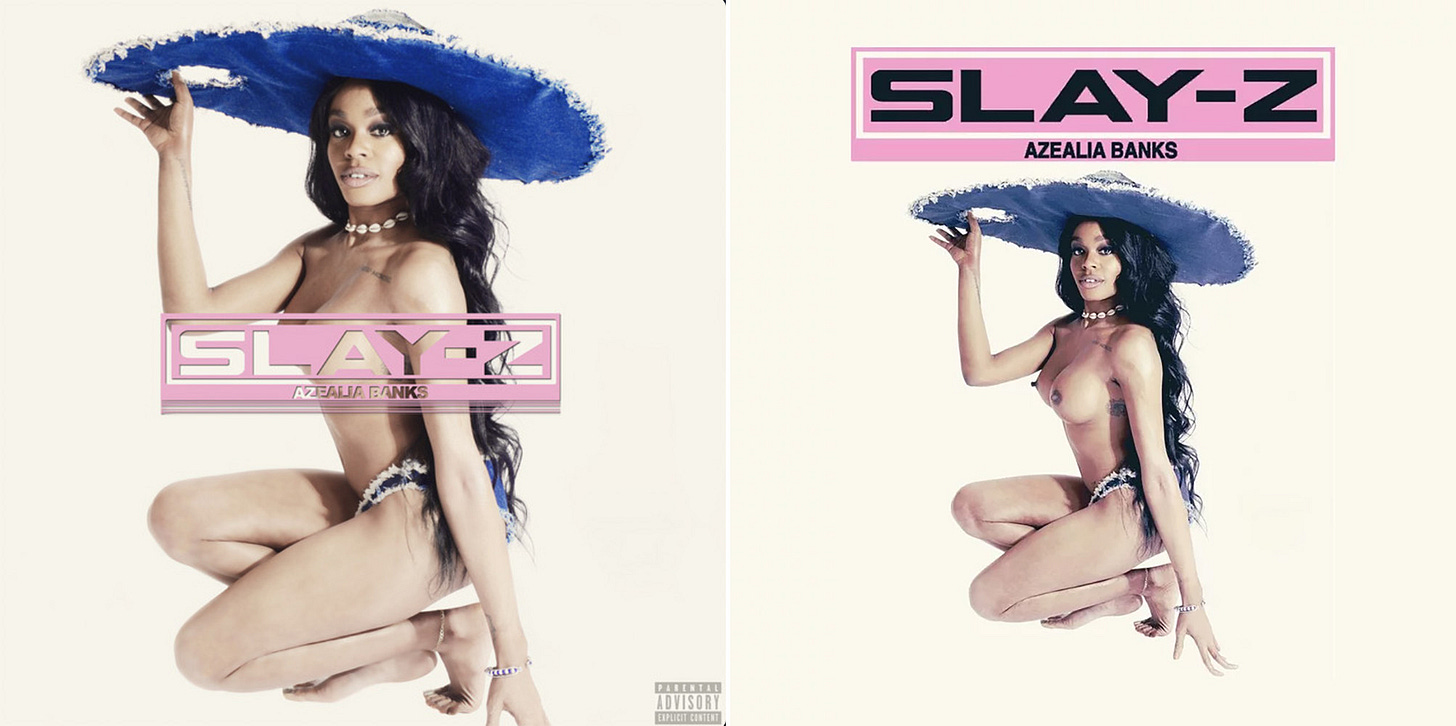

Hip-hop has its own range of controversial covers, ranging from early, sexploitation-nodding album sleeves like 2 Live Crew's 1989 As Nasty As They Wanna Be to Ice T’s 2006 Gangsta Rap. As women artists came to dominate the genre, they either conformed to or subverted (a tricky distinction) the nude album trope with gusto. Azealia Banks undressed for her cover of Slay-Z (2016) and prompted discussions such as VH1’s question to its viewers, “Is it empowering when female celebrities post nudes to social media?”

The term “empowering” has been a pesky parasite attached to every female disrobing as a way to either sanctify or vilify it, discarding every other motif for nudity as irrelevant at best, malicious at worst. What was not empowering is Spotify moving the title of the album to cover Azealia’s breasts, turning the cover from confrontational to coquettish and pushing it squarely into the male gaze territory.

Female artists are no strangers to selling albums with nude images on the cover — and it’s almost always a portrait of themselves. The intent of such images varies. The Slits, a fierce all-girl punk band who appear topless and covered in mud on the 1979 cover of Cut, come off as warrior Amazons whose nudity is more adversarial than enticing. Other artists, like Britney Spears, mimic the way the male gaze often objectifies female bodies. In Glory (2016) she presents herself as a sacrificial sex object and fully embraces the tired platitude that sex sells.

A few recent albums by women recreate the trope of objectification while declaring it a feminist victory. Selena Gomez was apparently talked into going fully nude for Revival (2016) and the outcome is low-key tragic. The cover's biggest mistake is that it tries to be “tasteful,” a most flawed ambition when it comes to nude photography. Selena is tastefully covering herself and the image is tastefully black and white but the result is both unsettling and sad. Looking at it makes me want to throw a robe over the singer and give her a hug. A similar pose by Lizzo on Cuz I Love You (2019), both fully nude and looking at the camera, has a an entirely different effect. Lizzo owns her space, and her body, and she confronts the viewer with a complex gaze. She is both vulnerable and completely in control. The image doesn't need art sauce or a show of modesty to excuse itself; the cover is unapologetic and gorgeous.

Beyoncé went (almost) naked for her recent album, Renaissance, and the image is being praised as an epitome of female self-empowerment. Ok, she is on a holographic horse and that's cool. But she is also dead-eyed and stone-faced while wearing a sexy Burning Man-style contraption. Beyoncé's cover fails because it plays it safe under the guise of being daring. The Lady Godiva persona has been used and reused so many times that even a holographic stallion can't save it. The pathos of the image is more reminiscent of the "I'm on a horse" Old Spice commercial that satirizes gender stereotypes than an expression of personal freedom (as claimed by Beyoncé).

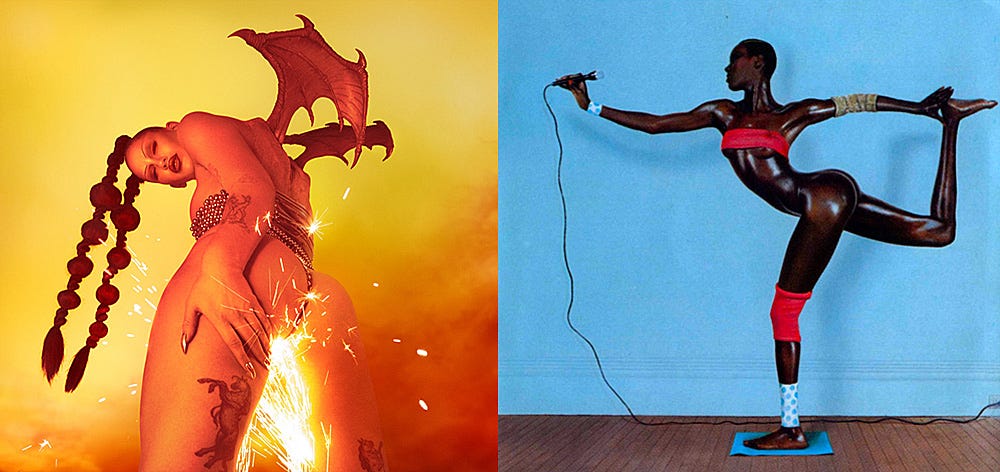

Here are two covers that are actually daring. Eartheater, an experimental artist who both croons and hollers like a banshee, is sending sparks out of her ass on the appropriately named Phoenix: Flames Are Dew Upon My Skin (2020). Self-aware, in control and with a fiery sense of humor, Eartheater achieves what Rosalia has tried and failed — a subversive female take on sexuality and objectification. Then there is the queen of them all, Grace Jones, on Island Life (1985), covered in oil and twisting herself into a shape no ordinary human should attempt. The cover is sexy while evading sexualization and strange while avoiding gimmickry. On top of it all, it is bitingly funny.

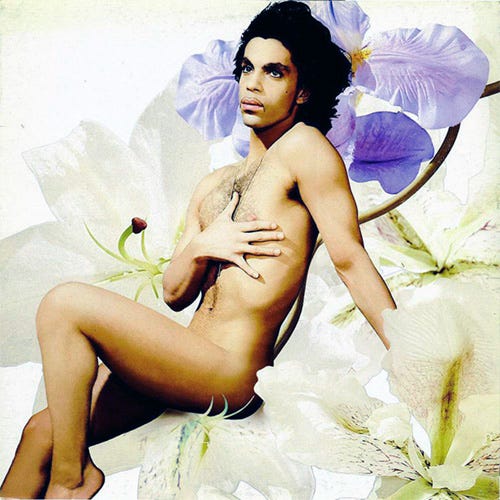

There also exists an elusive subset of male artists sexualizing themselves on album covers. Namely, Prince. His Lovesexy (1988) was removed from American shelves and covered in black paper to prevent outrage and fainting spells by sensitive shoppers. Prince is glorious, sitting on giant flowers and looking into the void with an evocative and vacant stare of a Pre-Raphaelite art model.

The recent addition to this tiny subgenre is Lil Nas X’s 2021 Montero, where the artist is levitating in the nude and resplendent in baby oil. But unlike the Prince cover, the nudity is too glossy to feel vulnerable, replacing intimacy with AI vibes.

The age of streaming made album covers more or less obsolete. That tiny thumbnail on Spotify is irrelevant (and censored if too risqué, as is the case in Azealia). Which is the reason I got myself a record player and a decent vinyl collection. Admittedly, I spend more time looking at the displayed cover of the moment than I do listening to it, but it restores the much-needed visual dimension to the music. Because even when the album cover is bad, it's still fun to look at and discuss (with a few exceptions — looking at you, Scorpions). Right now, Rosalia is on constant rotation and its strange cover is glaring at me from the record stand.

It's unfortunate when bad covers happen to good albums. But that doesn't make the music any worse, for the same reason that a beautiful photo of a naked woman can't make shitty music any better. Album design should be judged on its own merits — it's a visual art form like any other — just don't judge the album by its cover.

As I am doing research for my male gaze newsletter, which artists do you think wall into that category — men or women — and which do it well and which don’t?

Follow me on Instagram @dina_litovsky

This is a very interesting topic and great piece on something I haven’t seen raised before.

Most of these examples are cringeworthy, but I’ve always loved that Roxy Music one, which strikes me as campy and sexy without being fetishized. And that Grace Jones cover is brilliant.

let's not forget Blind Faith, which treads into probable illegal territory (https://www.amazon.com/Blind-Faith-CD-not-vinyl/dp/B077MN1HXY).