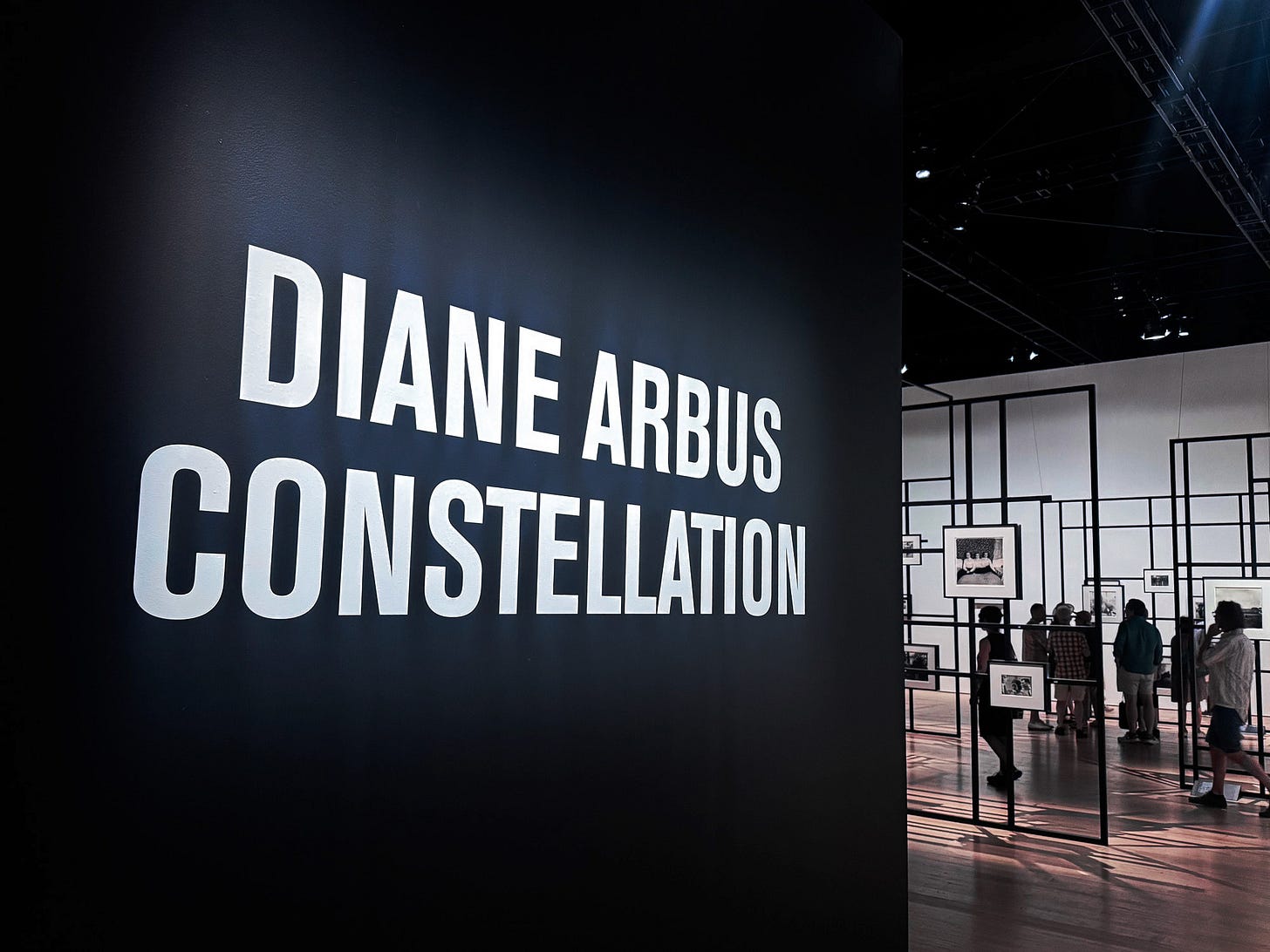

The Disappointment of the Diane Arbus Constellation at the Park Armory

I walked into the Park Armory Constellation exhibit as a Diane Arbus fan but came out riddled with disappointment and confusion.

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation

A curious thing happened. I walked into the Park Armory Constellation exhibit as a Diane Arbus fan but came out riddled with disappointment and confusion. I’ve seen a few of the portraits before, scattered in various exhibitions, and I’ve always liked their quiet power. This time was different. I felt nothing looking at the beautifully layered exhibition, drawing blanks even at the famous photos that I previously liked. As my husband and I wandered around in circles, I was consciously forcing myself to engage with the work but coming up with an emotional void and thinking it was, somehow, my fault. Then, Sasha spoke up, relieving me of guilt. “I don’t get it,” he said. “I usually like her work, but this doesn’t make sense.”

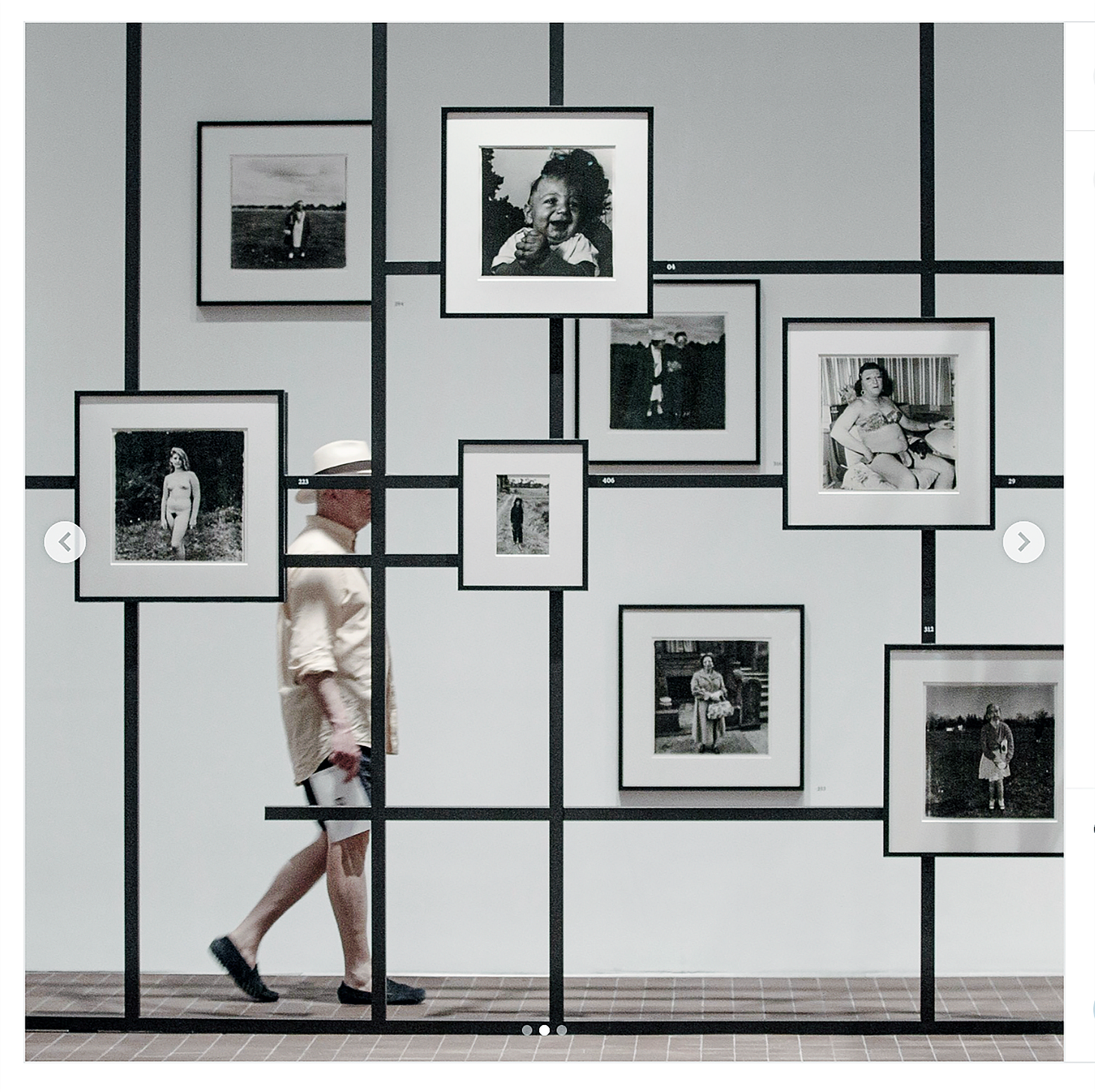

The exhibition itself is perfect social media catnip, a sculptural arrangement of square portraits hovering on metal scaffolding while the whole space is doubled in a full-wall mirror, giving it a feeling of infinity. That’s where the fun ends. The photos are thrown together without rhyme or reason, at least on the surface. They are neither chronologically nor thematically arranged, but at a closer look, I realized that the scatter isn’t random at all, it’s engineered separation.

It is no coincidence that no two photos of the same groups of people, whether nudists or people with Down syndrome, appear in the same visual space. There are plenty of such portraits, but all are separated as much as physically possible, giving the room a distorted vibe somewhere between Humans of New York and MoMA’s Family of Man exhibition. Both attempt, and arguably fail, to represent the human condition through a sweeping collection of portraits. The Constellation follows the same principle, using arrangement to create an artificial sense of togetherness, but the crowd of strangers is ultimately flattened by curatorial design.

When we first came into the exhibition, we thought it was huge, then realized the effect was created by a large-scale mirror. Though it looks cute, it didn’t make any sense with the photos themselves and felt like a gimmick.

Instead of aesthetic randomness, the scattering of portraits feels like a curatorial attempt at diffusing controversy that has haunted Diane Arbus’ work for decades. Coming from an upper-middle-class family, her stark photos of the poor, the disabled, and those on the fringes of society have long been accused of being exploitative to her subjects, positioning them as exotic “freaks.” I have always argued with that point of view, defending the portraits as raw, powerful, and empathetic. As I wandered through the exhibition, that feeling of empathy was all but gone. Most of the portraits in the exhibition have the subject looking deadpan into the camera, no emotion, no nuances, just a clinical gaze of a photographer to the subject and the subject to a photographer. When presented with just one or two of such photos, they appear dignified and powerful, but surrounded by dozens and dozens of the same deadened stares, the repetitiveness becomes formulaic. Many of the photos felt like an afterthought, badly lit and underexposed, and all haunted by the same neutral gaze, giving them a feeling of typology rather than individual portraits.

Official photo of the exhibition from Park Armory’s Instagram. Nudists, babies, performers, street portraits thrown in one cluster.

Most people wandered around aimlessly, seemingly as confused as we were.

By arranging the photographs in clusters, it seems that the curator tried to take the bite away, hoping that the lack of obvious themes and the aesthetics of the exhibition itself will blunt the uneasy emotion and difficult conversations that the photos inevitably provoke. For me, it has achieved the exact opposite. Diane Arbus had a personal obsession with looking at people outside of her social circle, documenting lives that would never intersect with hers if not for the camera, and that obsession is the saving grace of her work. Knowing her struggle with depression, resulting eventually in suicide, her portraits appear as a personal struggle to find a way out through the lives of others. The exhibition missed this entirely, trying instead to frame Diane Arbus’ work as a social document in the likeness of August Sander, the relentless documentarian of pre-World War II Germany. But Arbus didn’t pick her subjects to represent a broad sample of society, as Sander did. Instead, she gravitated toward isolated groups, often on the margins of society, and unlike Sander, her work, detached and voyeuristic, often fails the empathy test.

Patriotic young man with a flag, N.Y.C 1967 A subversive and grotesque take on patriotism. Diane Arbus would have had a ball at MAGA rallies.

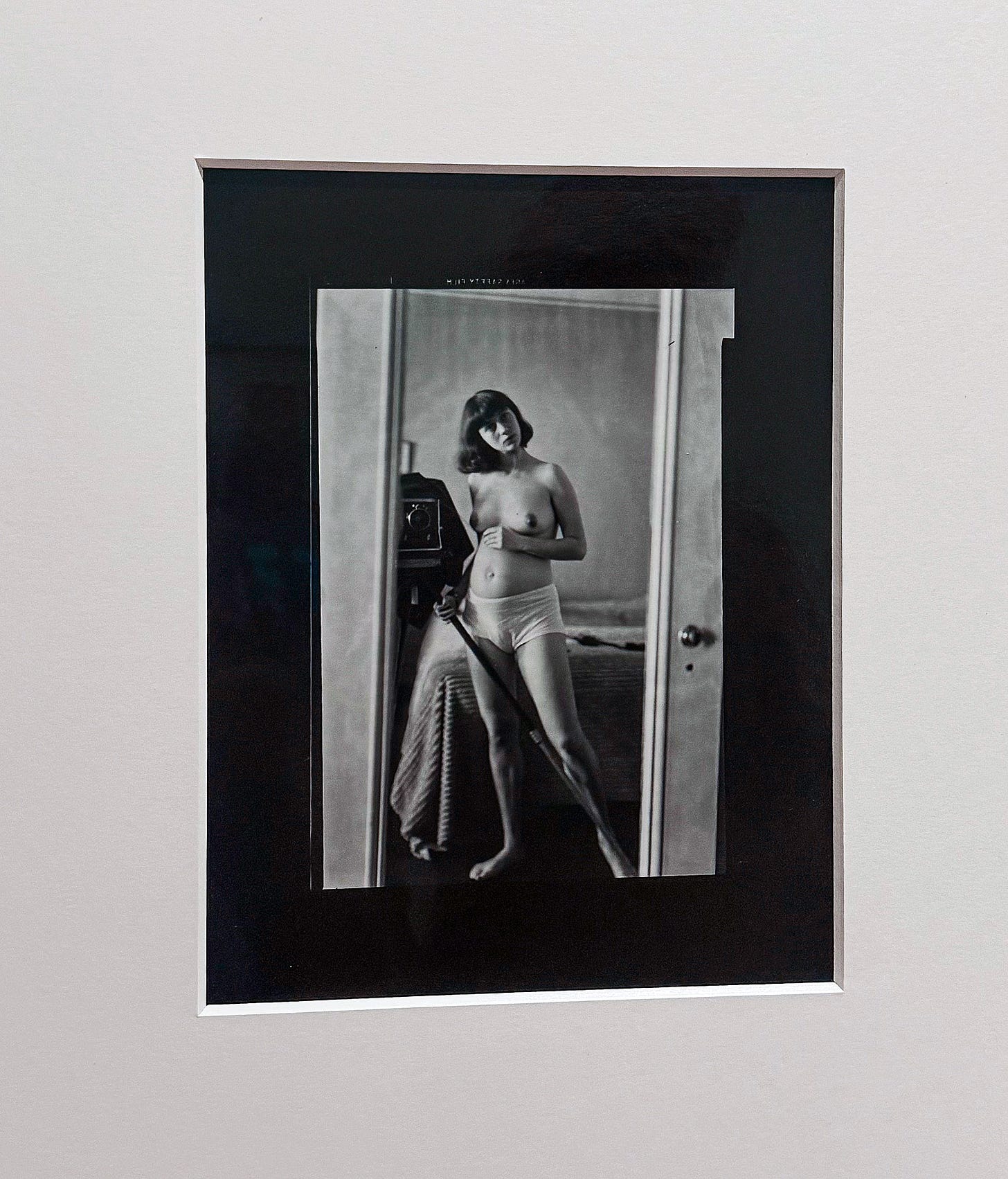

If the photos were placed in thematic groups, they would overwhelm the viewer but also highlight Diane Arbus’ compulsion in seeking out specific subjects. It’s only through such context and emotional unease that the work can move away from exoticizing the people in the photos, becoming instead a perpetual search for meaning. The only photo hinting at the highly personal nature of her work is the nude self-portrait of the pregnant Diane Arbus, looking at the camera with the same deadpan, unflinching stare. Unfortunately, that’s not enough.

Self-Portrait, Pregnant, N.Y.C., 1945

By trying to make the show palatable for 2025, the exhibition managed to divorce the images from both their context and their power. A nudist portrait on its own raises more questions than a dozen of such photographs exhibited together as a subculture. When presented as a community, the lack of individual empathy is replaced by a thread of compulsive fascination weaving through them all. But left to their own devices, many of the portraits feel fetishized and devoid of humanity.

Would I have enjoyed the photos better if they were direct in their presentation? Maybe. But even if I hated the work, it would have been better than feeling nothing at all. The curators did a disservice to Arbus by diffusing both her personal demons and the difficult but necessary conversations they would have provoked. Instead, the effect of these often disturbing portraits is zombifying, a deadened response to something that should have been visceral and emotional.

The Constellation, though aesthetically beautiful at first glance, is all smoke and mirrors, a curatorial attempt to coddle Diane Arbus’ difficult legacy.

A family one evening in a nudist camp, PA, 1965 The sparse landscape, the details of the slippers and sunglasses, create a strange, alien portrait.

Adolescent girl at a nudist camp, N.J, 1965. This portrait was hung so low that I almost missed it, and it felt like an attempt to both include it and obscure it. Arbus’ photos of nudist camps are less about nudity or specific individuals than about her fascination with community, showing its absurd normality without any sexualization, but that important distinction gets lost in the exhibition. There are plenty of nudist portraits in the exhibition, but they’re all spread apart so the feeling of community is obliterated, leaving the viewer stranded.

Man with safety pins, N.Y.C. 1962. An amazing thing happens when the best portraits get taken out of the exhibition, they get restored to their full power. The man’s expression is magnetic, soulful, so much so that it takes a few seconds to notice the safety pins. On par with the best of her photos, this is a provocation, inviting both the viewer and the photographer to face their own reactions to pain and spectacle.

The un-random randomness of photographs.

Sasha being underwhelmed

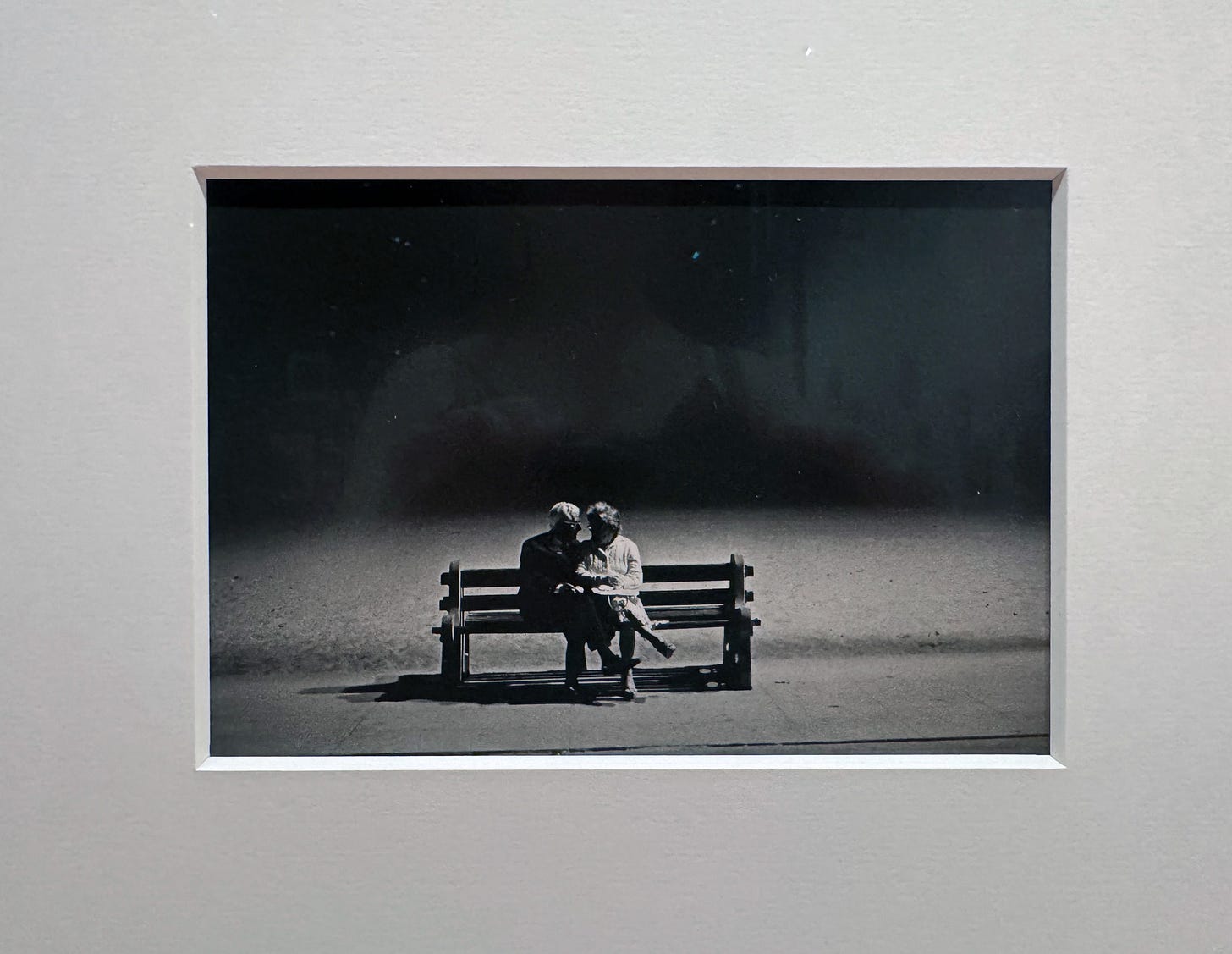

Old couple on a bench at night, Santa Monica, Cal., 1962 My favorite photo in the whole exhibition was a non-portrait, a faceless couple in an anonymous landscape, an image that’s both romantic and bleak.

Find me on Instagram

I was awestruck by her 1972 monograph when I got my hands on it as a kid and have been a fan ever since. Recently, I went to David Zwirner's revisiting of the 1972 retrospective at his LA gallery, and I was just as dazzled and moved. Yours isn't the first negative review of seen of the Armory show, and both your analyses certainly underscore the presentation aspect. The other essay on the show that I read also frowned on what they perceived to be as a cruel objectification of her subjects. I didn't feel that way at the Zwirner show. Maybe that's in part because of the way the show was hung, with lots of space and subtle framing and the opportunity to consider each subject in all their jolie laide glory.

I came away with similar feelings about the show. I thought there was something wrong with my eyesight because the room was so dim. Many of the photos were hung so high and low that I could not step back far enough to view them properly. There was no clear path through the exhibition, so I am not sure I saw it in its entirety.