Secrets in Photography and the Ethics of Influence

What photographers choose to reveal and why, and the blurry line between imitation and inspiration.

In the Flash is a reader-supported publication about intent and creativity in photography. To join the conversation

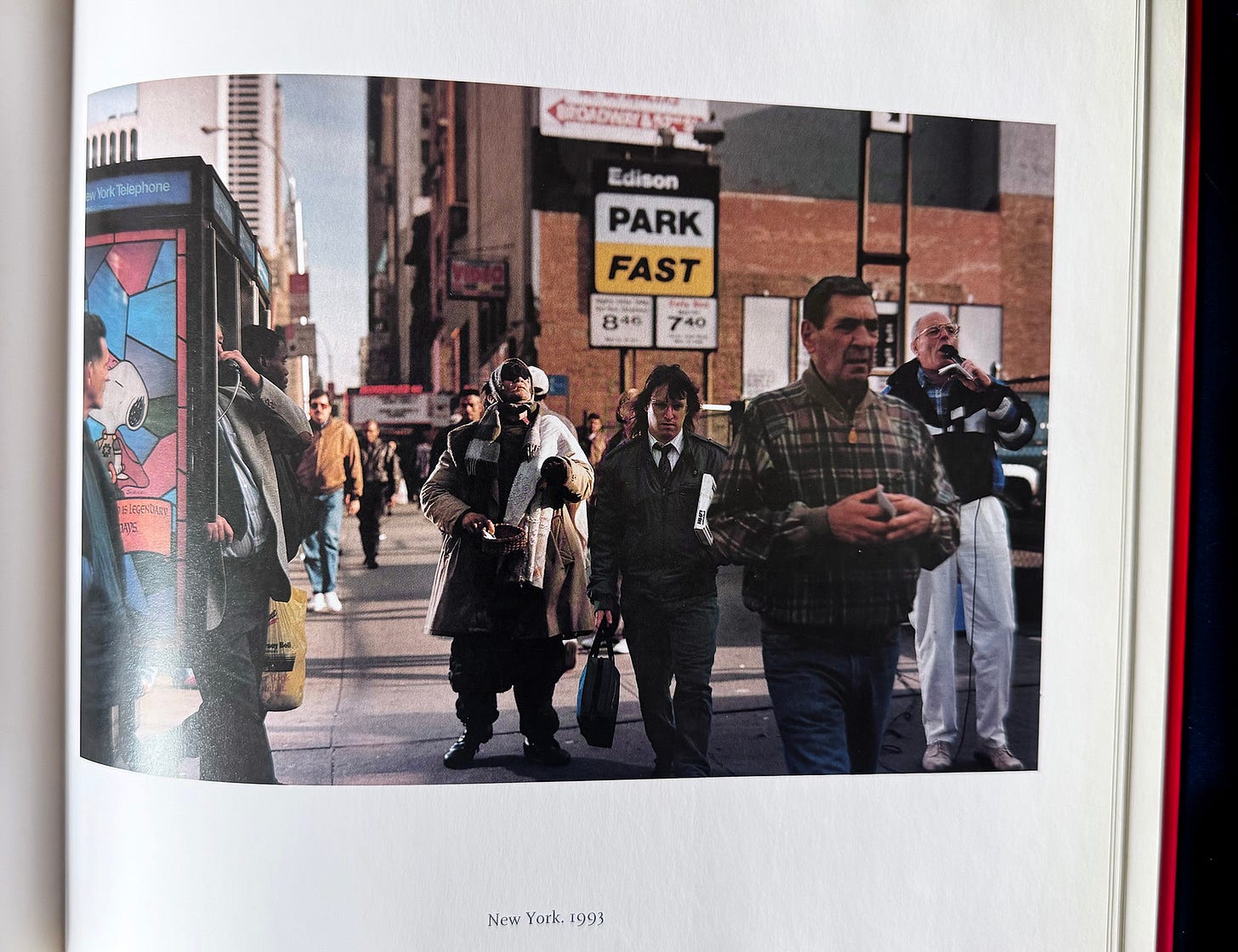

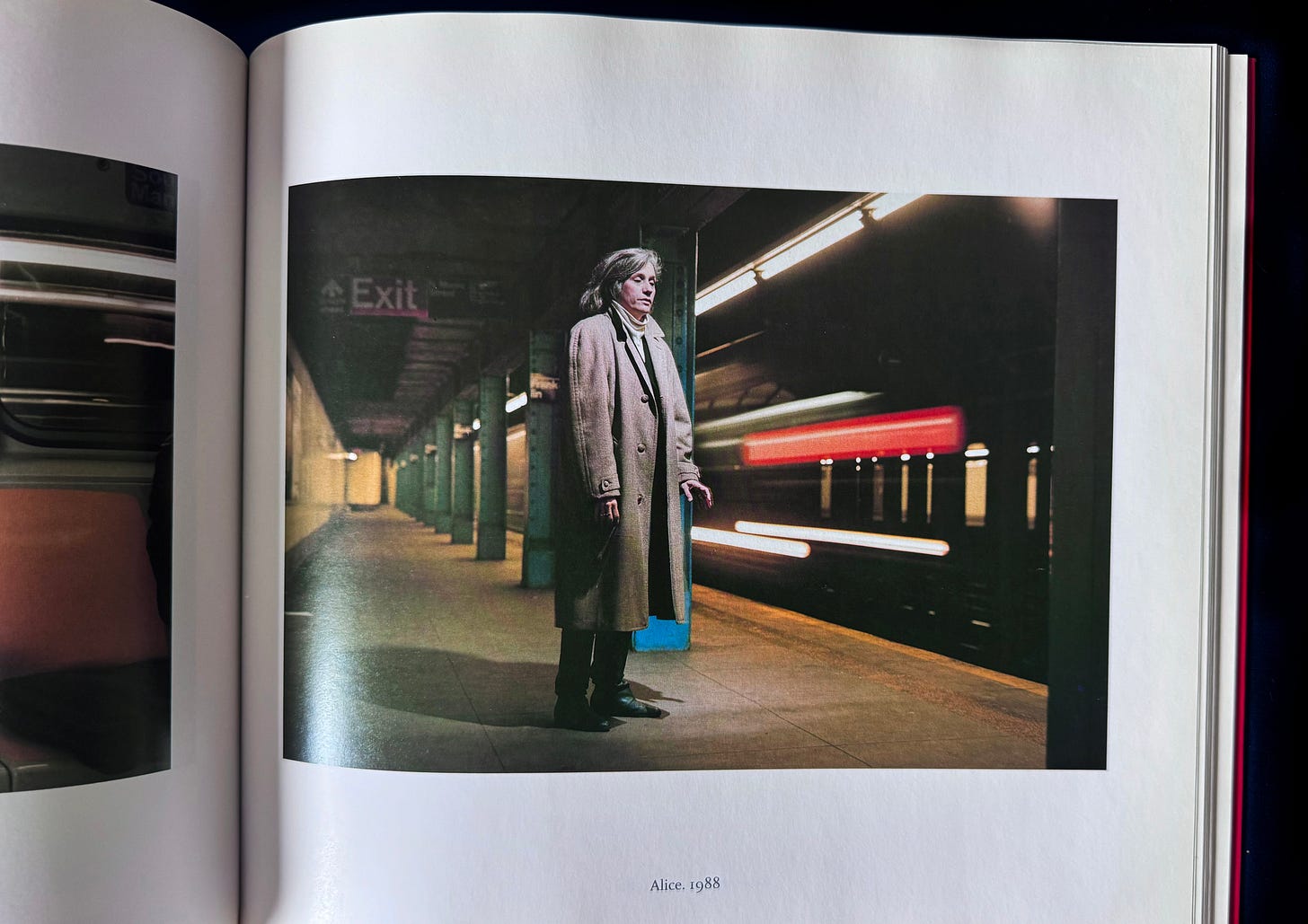

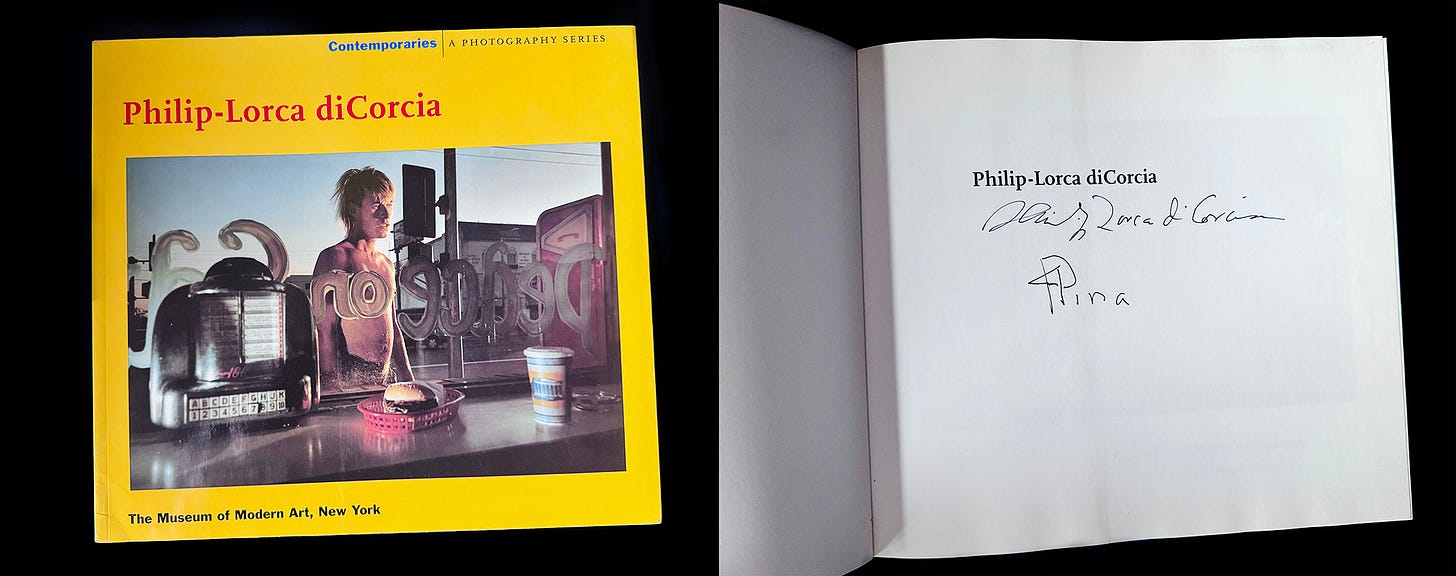

I was browsing through Substack, my preferred doom-scrolling platform, when I stumbled upon an article featuring moody, theatrically lit street scenes. I was sure these were the unpublished photos of Philip-Lorca diCorcia, one of my favorite photographers, but when I opened the feature, I saw that it was someone else entirely. The resemblance wasn’t superficial, it was structural. The photographer was using the same language of urban detachment and alienation in megacities, a similar choreography of strangers caught in psychic mid-sentence, and all of it was lit by remote-triggered strobes suspended above the passerby — Philip’s unique lighting method. It’s possible that the photographer independently stumbled on the exact aesthetic, concept, and method of Philip-Lorca diCorcia, done twenty years apart. But it’s unlikely.

What surprised me the most was that neither the photographer nor the author of the piece referenced diCorcia as an influence. This peeved me on a personal, petty level, since I’ve gone through a long, intentional struggle of making sure my work doesn’t imitate the distinct language of the very same photographer.

Philip-Lorca diCorcia has been one of the formative influences who redefined my approach to street photography. Before I discovered his work, I flaneured around as a Bresson-inspired documentarian, using natural light to catch natural moments. It didn’t give me much satisfaction. Then I saw diCorcia’s uncanny street scenes lit like theater stages, and I realized the wider possibilities of the genre. I wanted to do THAT. But of course I couldn’t because it was already done. Instead, I cannibalized bits and pieces, from the dramatic lighting to a hovering visual detachment, which have appeared in almost every project I’ve done since. One of my series was quickly abandoned because it came too dangerously close to diCorcia’s Heads. I was afraid of being the person making inferior copies of a famous photographer’s work, and even worse, being called out on it. So, when I saw the Substack, I felt a low-grade existential unease, as if I played by a set of rules that no longer, or never applied.

I’d bet that every photographer has experienced a variation of the same — someone else’s work triggering a burst of admiration, envy, and regret. It’s like discovering the potential future expression of your own ideas and aesthetics, with the caveat that someone else got to it first. So, what to do? What are the unspoken ethics of photographic influence? How close is too close when it comes to being inspired by someone else? And what role do secrets play in protecting our work?

My partner, Shane, is a magician, and we often discuss the weight, meaning, and safeguards of secrets in magic and compare them to photography. In the world of magic, secrets are experienced on a macro level as an existential glue that holds everything together. They serve to protect the collective tradition and ensure the continuation of the art form. The divide between those without secrets — muggles or laymen, as professional magicians call the rest of us — and those holding them is as vast as the blue pill/red pill experience. To explain to laymen how magic tricks work is an industry taboo, one that would get you kicked out of the (mostly) boys club. There are a few social media magicians who do exactly that, and they are universally reviled. One of the most popular ones, an account on TikTok with 1.1M followers, is the Mask Magician, a whistleblower who is appropriately masked and anonymous.

Photography, in contrast, doesn’t have the same obligation. Methods and techniques are public knowledge, while secrets sheathe personal interests, not the medium itself. They serve to preserve scarcity and, on an individual level, protect careers, authorship, and ego. It’s only when the photographer reaches the apex of their career that some share their secrets in order to ensure their legacy. A lot of the time, those secrets are less about photographic methods, since those are public knowledge, but an idiosyncratic way of solving problems. Weegee revealed his methods in a 1953 book, Secrets of Shooting with Photoflash, twenty years after he got famous for dramatic photographs of crime scenes and spectators. One such secret was his use of a police-brand shortwave radio, which allowed him to arrive at the scene faster than any other photographer.

When I started In the Flash, I made a conscious decision to be transparent about my thought process while including some technical details. The thought process is the most revealing thing any photographer can share, while the setup itself is the exoskeleton that can be shed at any moment. Early in my career, I lacked the self-awareness to do this because I was too sensitive about people imitating my aesthetic if I divulged too much. My process was simple: one camera, one lens, one off-camera flash. It didn’t take much to replicate, and it wasn’t mine to begin with — I macraméd it from my favorite painters, film directors, and photographers like Larry Fink, Alex Webb, Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Off-camera flash became editorial catnip, and soon enough, everyone was using it. In one case, a colleague told me she was asked to shoot in “Dina’s dramatic strobe style.” But no one knew who came first or who jumped on the bandwagon, and it didn’t matter, it was all fair game.

To shake things up, I stopped using flash in my personal work. It was a decision fraught with fear, because strobe was my aesthetic identity, and I was sure that I wouldn’t get hired without it. Instead of being a rebel on a job, I photographed Meatpacking, a project using the ambient lights of the nighttime city. Then came Dark City and Where the Amish Vacation, an assignment for the New Yorker, both done without strobes. Eventually, I came back to off-camera flash, but by that time the thought of being copied didn’t worry me because flash was no longer the only thing in my toolkit, and more importantly, I was a much more confident photographer.

My current “magic” setup is as close as I have ever gotten to a secret —a unique lighting process, one that is harder to guess or replicate than a lone flash. But though I pieced it together through a collaboration with Shane, none of its pieces are original. Plenty of photographers use the same elements, from prisms to gobos to plastic materials. What makes this setup mine is combining all these together to achieve a (still somewhat blurry) vision using magic as a foundation.

Another secret has been showing magic to my portrait subjects in order to take the fourth wall down and to photograph unique expressions only possible when seeing solid objects appear and disappear in front of your eyes. I didn’t tell anyone about this process for the first year. When I finally decided to write about it, Shane was apprehensive that this would allow someone to "steal” the approach. He has been burned a few times in the past when magicians tried to copy his unique card handling and pass it off as their own (including secret videotaping of shows or calling his colleagues to fish out his technique). That’s not how photography works, I told him, but then I started wondering, how does this actually work in our industry?

Like photography, magic doesn’t have unions, but it also lacks copyright laws. Instead, they are a self-governing body, and if a magician is caught stealing, they get blacklisted by the industry. Gossip and punishment travel hand in hand. I’ve never heard of that in photography. When someone’s style is too close to another artist, the conversation gets padded with euphemisms of inspiration and influence, and sometimes simply ignored. The only person who receives universal ire is Richard Prince, and that’s for blatantly appropriating other photographers’ works. But in spite, or rather because of the controversy, Prince has been selling his prints for exorbitant sums, thus securing his reputation as an artist.

If Prince’s brazen thefts triggered industry outrage, one of my favorite musical artists, Richard D James, known as Aphex Twin, offered something just as radical in the opposite direction. James had this to say about his favorite musicians,

“This is music I enjoy. Not influences. I hate the idea of being influenced. The thought of putting bits of other people’s music into my own makes me sick.” (Q Magazine (March 1994)

Such mindset requires a delicate combination of genius, ego and madness, and one that make the rest of us feel like draftsmen. In contrast to this infuriating, envy-inducing statement, most artists share the views closer to Austin Kleon’s Steal Like an Artist which became a New York Times Bestseller and emphasized the myth and futility of pure originality. But Austin did draw a line between plagiarism and emulation as the distinction between copying someone else’s vision and methods vs reverse-engineering them. The idea that stealing from one person is plagiarism but taking from many is research, has been echoed by many people, and one that has fascinating implications if you extend it to AI and intellectual property (I’ll tackle it in another newsletter).

Originality in photography is a fragile currency. It is not achieved through secret methods or techniques, but a painstaking excavation of personal vision from other artists’ aesthetic debris. No secrets can protect someone’s brand because photographic style is contagious, and once a trend starts — whether it’s an off-camera flash or a desaturated portrait aesthetic — it can be hard to tell where innovation ends and imitation begins.

All photographers take from one another with impunity. Artists who reach a certain level of visibility inspire countless deviations. Gregory Crewdson, Bruce Gilden, Nan Goldin, Alec Soth, Alex Webb, and William Eggleston have all galvanized armies of young photographers to emulate their aesthetic. The best ones eventually separate themselves from their idols, inserting enough of their own voice to develop a visual language that feels distinct enough to matter.

In the end, people respond best to new ideas and visuals, not recycled versions of things they already love. This may be the only real governing principle photography has. Though the audience may like work done in Crewdson’s or Goldin’s style because it hits on already existing pleasure centers, and magazines may hire someone because an aesthetic fits their need of the moment, that photographer rarely builds a lasting career or legacy of their own. While no one gets punished for using someone else’s voice in photography, they end up sliding into irrelevance.

In a medium where everyone steals, the only real distinction is who gets remembered.

How I Pieced Together a Personal Style in Photography

Find me on Instagram

Oh damn, that last line is everything. Always enjoy your philosophy and your writing. Also, I remember really loving Soth's photography when I first saw one of his photos 20 years ago. But I had no idea how well-known and esteemed he was until a few weeks ago when we attended a talk he gave at our local art museum, so I chuckled at my ignorance again when you referenced him. During his talk, we were seated near a dark marble wall. As many in the audience lifted their phones in front of me to take pics of him on stage, i noticed the reflection of Soth and the gal interviewing him perfectly placed on the marble wall next to us, so I caught the image and it's become one of my favorite photos. I've always loved photographing reflections, but I'm also a timid photographer who doesn't want to feel invasive. . . and your post made me realize that beyond technique, those two aspects may be what makes me "me" in art. Thanks!

Thanks for the reintroduction to Philip-Lorca diCorcia. May I suggest The Continuing Moment by Geoff Dyer. It helped me come to grips with the influence of Harry Callahan on my own vision. Btw, I love your "secret" lighting technique. There is a beautiful fusion of movement that sneaks by the strobes ability to capture the microfraction of a second. Superb.