Confessions of a “Pupparazzi," From Westminster Show to Dog Parks

And my first published essay in Thames & Hudson,

Welcome to In the Flash, a weekly, behind-the-lens dialogue on photography. To join the conversation.

A couple of months ago, an essay I wrote for this newsletter got published in a Thames & Hudson book, Why We Photograph Animals. The irony, of course, is that I am not an animal photographer, nor do I consider myself a writer. But here I am, holding a hardcover Thames & Hudson book compiled by Dr. Huw Lewis-Jones, with a few pages of my writing and photographs of dogs, rats, and owls. The book contains three of my newsletter posts on animals compiled into one long-form essay. One of them is Confessions of a Pupparazzi, recounting my experience of photographing lots and lots of dogs.

Known for his witty street photos of dogs, Elliott Erwitt once said, "I like dogs because they don’t object to being photographed and because they don’t ask for prints." This might still be true of dogs themselves, but their owners, especially those who oversee their pooches' Instagram accounts, are a different story. When I was photographing dog parks for TIME magazine, I got called “Pupparazzi.” The times have changed since Erwitt's anonymous canine photos — every self-respecting modern dog expects to be tagged on social media.

Before I continue, a disclaimer. I am a devoted cat person. Living with a canine in an East Village apartment never seemed like a good idea. Yet, East Village is dog central, and every day I watch people pick up after their precious pets with a mix of admiration and bemusement. There are a couple of Dalmatians I bump into on my morning coffee walk who are so beautiful that I find myself daydreaming about adopting a puppy, watching as it becomes best friends with my two playful felines, and refocusing my photographic energies on making them Instagram stars. But that's just not my life.

As I went out to photograph in dog parks, I started thinking about what would make a portrait of a dog interesting. Can we even consider an animal photo to be a portrait? I imagine it depends on which animal and the extent to which we can anthropomorphize a species. We tend to view cute animals as having greater complexity and empathize with them by assigning to them human-like qualities. And we are more in tune with those animals we treat as pets, becoming familiar with expressions that we would otherwise miss in another species. It's probably easier to conceive of a cat portrait than one of a snake or a hippo. A close-up of a cobra would struggle to hint at the “inner” reality of the animal, but any cat owner can instantly recognize, in relaxed whiskers and squinty eyes, a very content, good-natured feline.

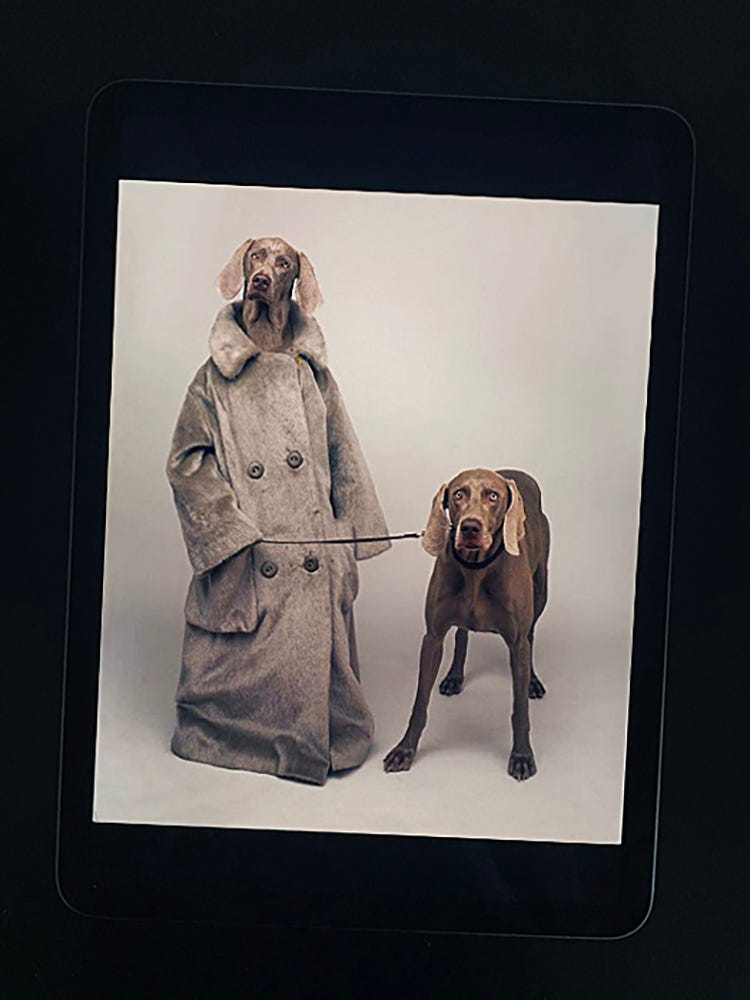

Dogs are easy to anthropomorphize, and we love doing so with them probably more than any other animal. William Wegman takes the Best in Show prize; his photography has exhausted every possibility of how to dress up his Weimareners over a period of 50 years. The humorous images occupy a netherworld somewhere between a portrait, a fashion editorial, and a meme. They could seem gimmicky at first, but under the layer of slapstick lies a tongue-in-cheek metaphor of the human condition. We are not laughing at the dogs, but at ourselves reflected back to us in canine form.

Gary Winogrand had this to say about dog photography: "Beware of pictures of dogs and children. They are not as good as you think they are." That perfectly echoes my cardinal fear when photographing animals—the inevitable pitfall of making cute photos. It is harder for me to take an interesting portrait of a cat because my overwhelming desire to hug them results in boring, nauseatingly sweet postcards. But dogs are a different story. I am curious to know more about them, and I can certainly keep my cool. Both of us are just sniffing out one another.

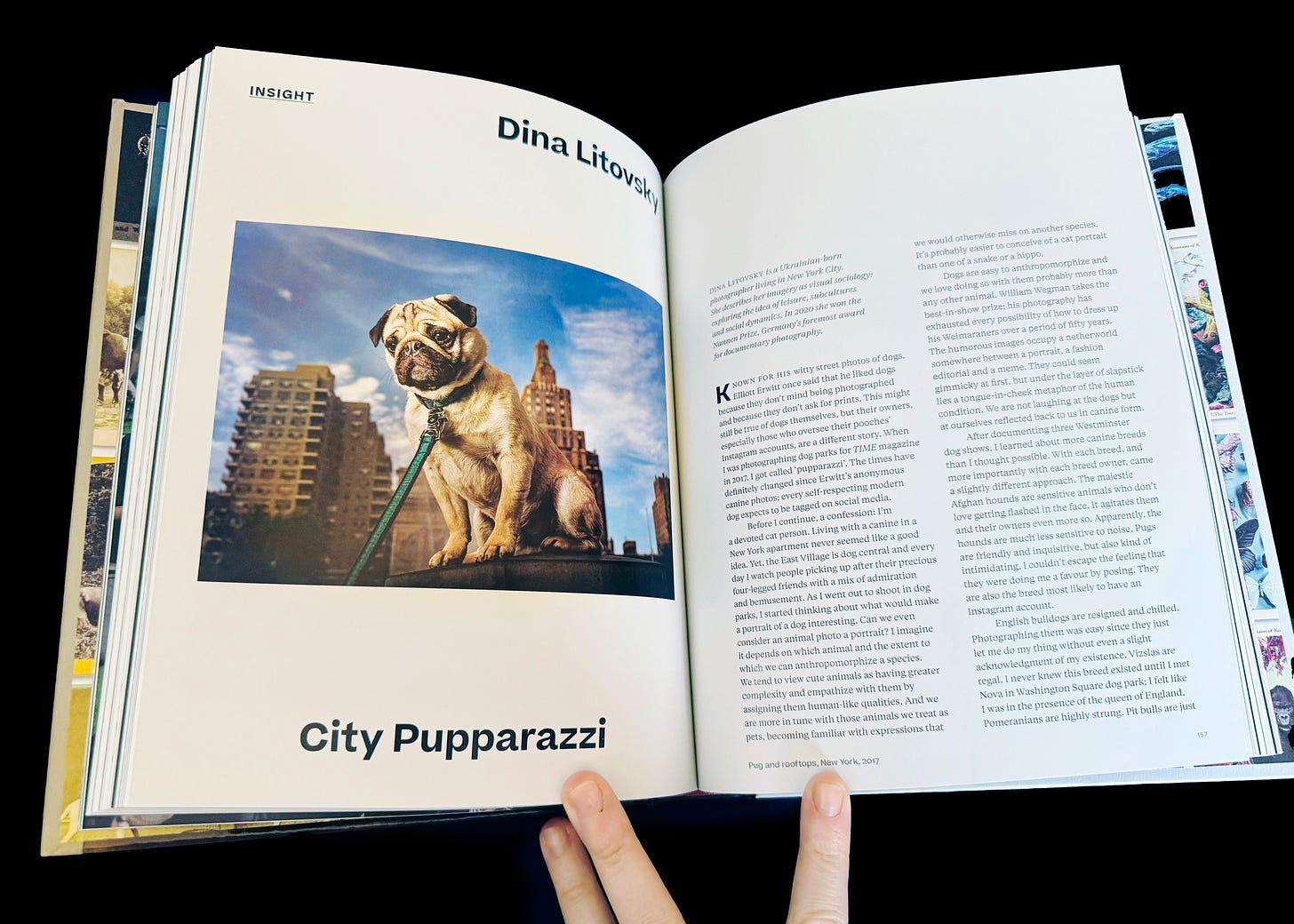

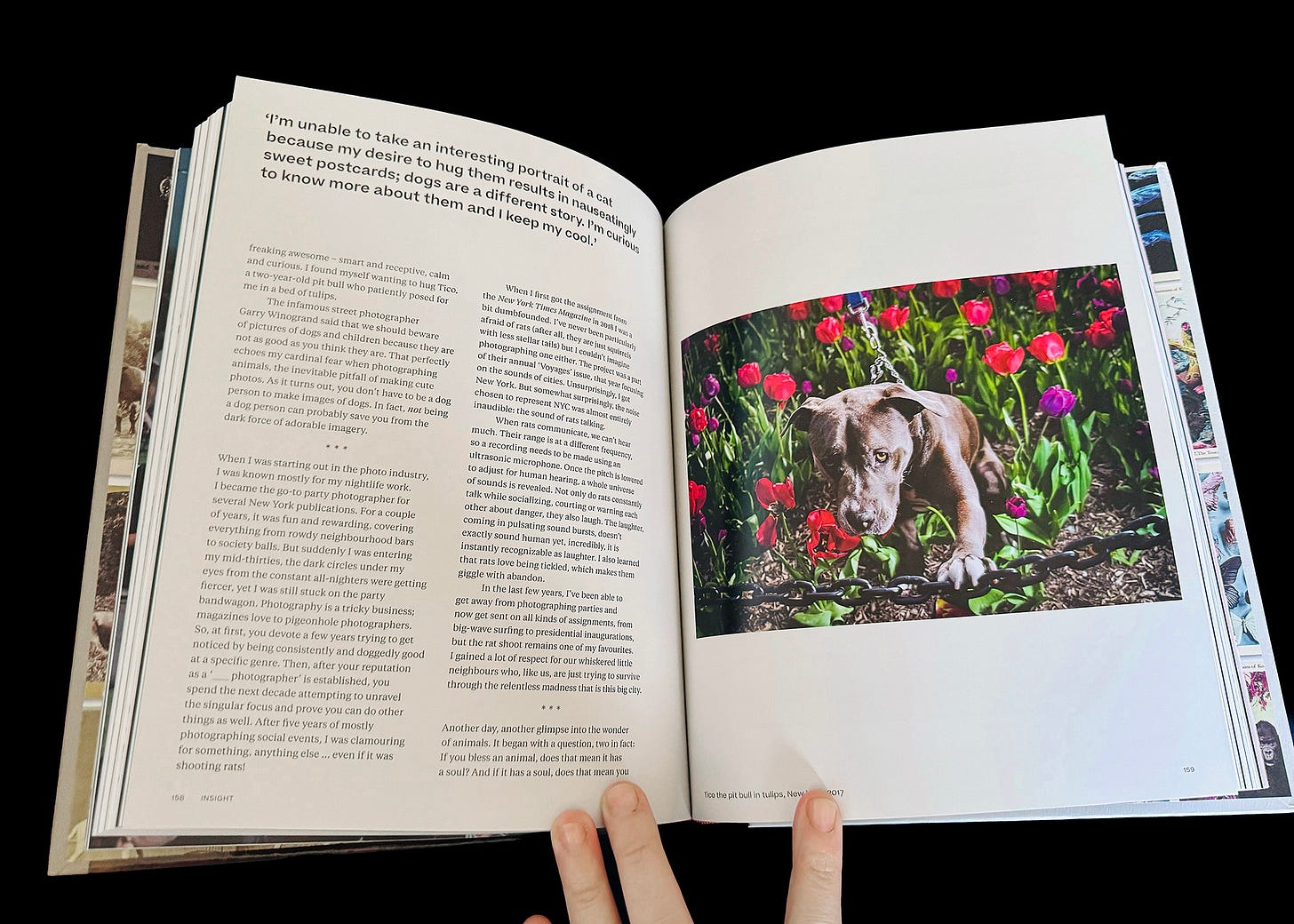

After documenting three Westminster shows, I learned more about canine breeds than I thought possible. With each breed, and more importantly, with each breed owner, came a slightly different approach. The majestic Afghan hounds are sensitive animals who don't love getting flashed in the face. It agitates them and their owners even more. As I wandered into the Afghan Hounds row at Westminster with my off-camera flash in hand, I got yelled out of there. Apparently, the hounds are much less sensitive to noise. Pugs are friendly and inquisitive, but also kind of intimidating. I couldn't escape the feeling that they were doing me a favor by posing. They are also the breed most likely to have an Instagram account. English bulldogs are relaxed and chilled. Photographing them was easy since they just let me do my thing without an even slight acknowledgement of my existence. Vizslas are regal. I never knew this breed existed until I met Nova at Washington Square Dog Park. I felt like I was in the presence of the Queen of England. Pomeranians are high-strung. I had to roll around on the grass for an uncomfortably long time trying to keep up with what looked like a furby (did I just date myself?) and had the pent-up energy of a squirrel on cocaine. Pit bulls are just freaking awesome — smart and receptive, calm and curious. I found myself wanting to hug Tico, a 2-year-old Pit Bull who patiently posed for me in a bed of tulips.

We consume most of our animal photos through social media. Dog posts rule the social media universe, with millions of dog content shares on Instagram and TikTok, but cats have been steadily encroaching on this dominance of canines. Doug the Pug, used to be the most popular animal, with more than 3.6 million followers, but he was recently put in second place by Nala Cat, boasting over 4.5 million. In the name of research, I spent some time looking at several of these obscenely popular canine mega-accounts. What struck me is how intentionally unphotographic the imagery is: no filter, a DIY aesthetic, and the optimistic light of a Christmas morning. It's the dog-next-door look—relatable, approachable, and heavily anthropomorphized. The dogs are dressed up like children, put in various “human” situations, and given a voice through inspiring quotes from a canine point of view. They lure us into identifying with the animal — a most clever ploy (as I write this, a Grumpy Cat dress hangs in my closet). But such imagery, with its primary objective to reach an abominable height of cuteness, is a far cry from the kind of photos I am interested in making when working with animals.

As it turns out, you don't have to be a dog person to make images of dogs. In fact, not being a dog person can probably save you from the dark force of adorable imagery. People make all kinds of assumptions about cat vs. dog people. I'm supposed to be aloof, introverted, and impervious to joy. The last one is outrageously erroneous (the first two are correct). I enjoyed rolling around on the grass with the feisty Pomeranian, getting a high five from the Pit Bull, and meeting all kinds of playful, lively, curious, and highly intelligent canines at Westminster. I came to love and admire dogs.

Having said all that, I still, steadfastly, refuse to ever pick up after they’ve done their business.

Westminster Dog Show for National Geographic

Inside the Minds of Dogs for TIME

Why We Photograph Animals, Thames & Hudson

Find me on Instagram @dina_litovsky

Oh my goodness!!! Adorable!!!

Love the photos and your perspective. I am also a cat person, aloof maybe sometimes, an introvert totally, but not impervious to joy at all. I’m also a photographer who loves making photos of my cat, both the cute for funsies type, and more interesting takes. I find it’s a fun challenge to try to make more interesting portraits of her, even if she is constantly impatient with me hovering with various cameras. I would love to see how you would photograph cats! Either out in the world or at home.